TV Representations of Autism Spectrum Disorder:

- IJCMR

- Apr 23, 2022

- 37 min read

Updated: Sep 16, 2022

A Cross-Cultural Analysis of South Korean K-Drama ‘It’s Okay to Not be Okay’

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33008/IJCMR.2022.01 | Issue 8 | May 2022

Amber Wisteria (Bath Spa University)

This work is one of two 2022 winners of our Centre for Media Research Student Award, a special prize awarded to a Media Communications student each year whose dissertation research shows exemplary quality, scope and ambition, and which has also been creatively reimagined to engage and benefit a wider industry audience. The winner of the Student Award is invited to publish their dissertation research alongside their accompanying creative project, and this work is also presented at our annual Degree Showcase event.

Abstract

This research took the form of two stages. On an academic level, it seeks to uncover the links between representations of ASD TV through a Cross-Cultural analysis of South Korea (SK) and the West by utilising a case study It’s Okay to Not be Okay. An argument is made that the case study represents an accurate understanding of ASD, but also of the family values surrounding it, such as the relationship those with ASD have with their family and siblings. Through a textual analysis, it was uncovered that the case study has accurate portrayals of ASD through its character Moon Sang-Tae (Oh Jung-Se). Not only this, but realistic portrayals of the relationship between family and siblings of disabled persons was uncovered, mainly relating to the character of Moon Gang-Tae (Kim Soo-Hyun). A reception analysis was then undertaken to understand if and how audiences in South Korea and the West reacted to these portrayals. Western/International audiences openly discussed the portrayal and family relationships and believed it to be accurate, as well as educational. South Korean audiences were reluctant perhaps due to a more conservative culture, to discuss the representation of ASD as well as the sibling-caretaker relationship. Therefore, there is a cultural difference in the way in which audiences interpret and understand representations of ASD, as well as familial relationships around those with ASD.

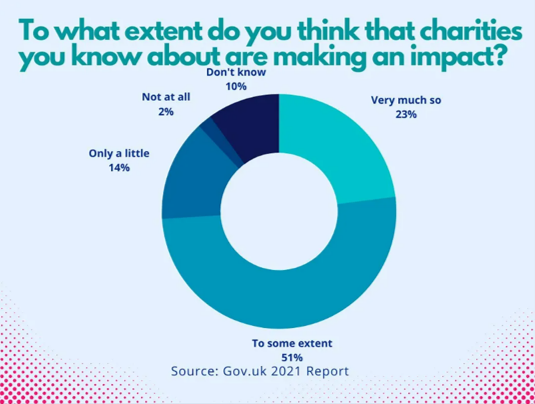

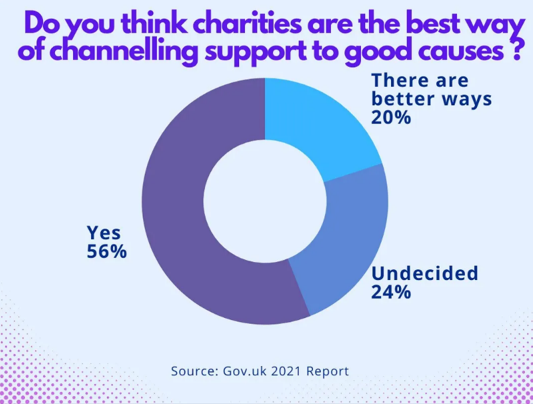

On a second level, and going beyond an academic dissertation, this research undertook industry research into the charity sector, focusing on Autism Speaks, in order to develop the conclusions from the research into a practical and factual awareness campaign about autism representations that introduces broader audiences to concepts of personability with diverse content and even taking in stories and accounts of those with ASD or the people around them. In a similar direction to Autism Speaks, short blogs or articles about understandings of ASD were used, expanding and improving perceptions of ASD on a cultural level. In doing so, not only have I broadened my understanding of the literature in my dissertation, but also have opened it up to feedback from audiences about how it may affect their lives.

Below is documentation of the awareness campaign work for Instagram, which includes interviews with the community, research into the relationship between the charity sector and perceptions of ASD, and other analysis. You can read the project's accompanying blog posts, which examine culture and ASD, highlight wider community interviews and propose strategic advice for the charity sector, online: https://amberwisteria.wixsite.com/portfolio

You can also follow Amber's research on her Instagram, which currently focuses on representations of Autism Spectrum Disorder on screen: @letschatrepresentation

Beneath the social media content you will find the complete dissertation in full.

Introduction

As more research into ASD is available to the public, there is more of a push to offer realistic portrayals of those with ASD, rather than the stereotyped, entertainment based ones.

The aims of this research are to uncover the prevalence, common understanding and appreciation of ASD in South Korea (SK) compared to the UK/US, through the usage of the case study of a TV drama It’s Okay to Not be Okay (2020) where ASD is presented in the form of one of the main characters. Also called I’m psycho but that’s okay in a direct translation from the Korean Hangul 사이코지만 괜찮아. This dissertation seeks to understand any cultural difference audiences might have about representations of ASD, as well as the family relationships surrounding those with ASD. By utilising this case study as a focal point, reviews will be investigated, and differences in expression of understanding or appreciation of the representation of ASD and the familial relationship surrounding it will be researched.

Literature Review

1 Autism, Social Theory and Sibling Studies

1.1 Autism and its definitions

Autism Spectrum Disorder, henceforth mentioned as ASD are a group of neurodevelopmental disorders including autism itself which derive from differences in the brain, sometimes stemming from genetic conditions (NHS, 2021, CDC ,2021). Causes of ASD are not conclusively known, but research into the levels of ASD which has been assimilated into the term of ‘spectrum’ to describe the overarching neurodevelopmental conditions (CDC, 2021, Troyb et al, 2011). While symptomatic expression of ASD can be very dependent on case, there are certain symptoms which are seen often, such as repetitive behaviour, difficulties in communication and socialisation, aggressive behaviours, restricted interests, or hyper-focused interests, (Honey et al., 2007, Zandt, Prior, and Kyrios, 2007, Worley and Matson, 2012). While this list is not exclusive to symptomatic expression of ASD as a spectrum disorder, it provides an indication of relevant behaviours expressed.

1.2 Sibling studies

McLaughlin et al., (2008) report that siblings feel the burden of their disabled sibling and often must grow up while being a partial carer for them. Siblings often feel invisible in the eyes of their parents and pity their disabled sibling for their ailments (Mclaughlin et al., 2008). Studies have indicated that the ‘non-disabled sibling may encounter less parental attention, increased care responsibilities, risk for poor peer relations, lower level of participation in outside activities and loss of companionship’ (Wolf, et al., 1998 cited in Naylor and Prescott, 2004). It was discussed that siblings felt like they were expected to be involved in helping their disabled sibling and were under increased pressure to perform either academically or in sporting activities to compensate for their disabled sibling, or to attempt to gain attention from their parent/s (Nixon and Cummings, 1999, Naylor and Prescott, 2004). Furthermore, but they felt that their free time was taken up by their disabled sibling (Naylor and Prescott, 2004).

There are also developmental problems associated with the siblings of disabled children with intellectual disabilities, including difficulties with social skills and behaviour problems, especially when the disabled sibling is older than them (Begum and Blacher, 2011). It is also noted that in adulthood, when the parents are no longer able to be a caregiver, siblings assume to have to hold an involved caregiver role and tend to have less of an emotional connection with their sibling as well as being more pessimistic about the future (Orsmond and Seltzer, 2007). But the studies’ findings were not all negative, it was found that siblings were more empathetic and open-minded, especially in terms of understanding disability and the importance of inclusion (McLaughlin et al., 2008, Hodapp et al., 2010).

2 Cultural standpoint and differences between UK/US and South Korea

Mandall and Novak (2005) detail that there may be cultural differences in the understanding, recognition, and treatment of ASD. They discuss the reasons behind this and resolve that it may be due to familial influences and the way symptoms are viewed. Cultural acceptance of certain symptoms may occur, as certain cultures express these symptoms as just a result of upbringing or a result of their environment, such as inability or difficulty in communication and social skills. This may also similarly occur with how much certain cultures accept the views of modern medicine and academic research. Countries also have their own methods and categories of diagnosing ASD which can also lead to different statistics and views of ASD (Matson et al., 2011). Daley (2002) comments that while ASD and other pervasive developmental disorders occur similarly in different cultures, the symptomology seems to differ based on location and on reflection, culture. They also note and concur with Lotter (1980) that parental education may play a factor on openness to accept that their child has ASD.

In a study by Matson et al., (2011) they approach a cross cultural examination by first dictating a generalised measurement of ASD, a 19-item checklist established as the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000). Using this generalised measurement they assessed participants from the US, UK, South Korea, and Israel. Participants from South Korea (SK) scored higher in items around communication and understanding, such as age-appropriate self-help and adaptive skills, verbal communication, language, expecting others to know their thoughts, experiences, and opinions without communication, and understanding age-appropriate jokes, sayings, or language development (Matson et al., 2011). These can more aptly be called social skills and dictate that those with ASD in SK are more likely to have a better understanding of social skills. As this was lower in both the US and UK, Matson et al., conclude that cultural differences, parents’ expectations, and different diagnostic screening for countries were the factors involved in these differences. In a follow up study completed in 2012 by Chung et al., they seek to understand the cross-cultural differences in challenging behaviours in children with ASD, taking the same four countries into account. Compared to the UK and US, the participants from SK showed noticeably fewer challenging behaviours which may also be attributed to cultural factors, or a resistance against the diagnosis or treatment of those with ASD in SK.

Encapsulating these studies and a study by Scarborough and Poon (2004) and Kim et al., (2011) locate culture to play a large role in the presentation of behaviour and development. Not only this but the cultural result in parents’ resistance to diagnostics and treatment is a contributing factor.

3 Autism in the media

3.1 General Outlooks

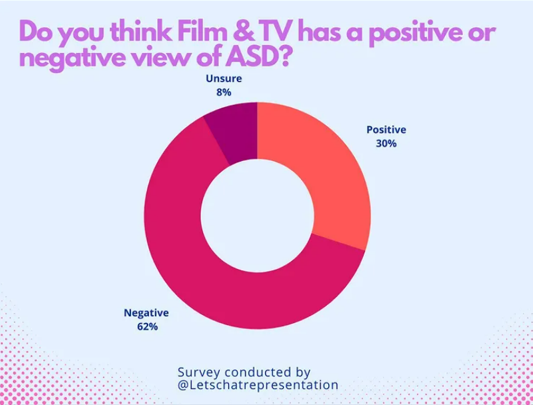

Those with disabilities have often been a marginalised group, and the ways in which disability is represented in the media influence and shape the perceptions of disabilities to a wider audience (Dean, Nordahl-Hansen 2021). Draaisma (2009) conceptualises ASD representations in film and TV into stereotype categories (Draaisma 2009). Draaisma reflects on many media representations of the ‘savant’, one who is incredibly gifted, or someone who is an anti-social, awkward member of society (Draaisma, 2009, Dean and Nordahl-Hansen, 2021). But there is also another flaw with even more recent interpretations of ASD on screen, where the diagnosis of ASD comes as something that completely changes one’s life, and becomes a disease that either the character or those around them should seek to cure and treat; which reflects a call to the audience to attempt treatment and curing of those with ASD around them, creating an environment of attempting to fix someone with ASD rather than accept them (Poe and Moseley, 2016).

3.2 Representations of Families of those with ASD

While there is not a lot of research into the on-screen dynamics of the family unit with a child with ASD, Allen (2017) discusses the dependency seen on screen for maternal nurturing, and how ASD is seen as ‘the big bad monster’ for the family environment (Allen, 2017). He comments that ‘Lifelong autistic dependency confounds popular autism narratives that promise to cure or significantly mitigate autistic symptoms through biomedical or behavioural interventions in childhood’ (Allen 2017). Often adult representations of ASD are those dependent on their caregivers, and that treatment and cure at the childhood stage would have negated the ‘monstrous’ adult with ASD (Kittay 2001; Simplican, 2015, Allen, 2017). Simplican also argues that the person with ASD and their caregivers reflect insensitivity and destructive tendencies towards each other (Simplican 2015). These struggles fluctuate and introduce a difficult balance that becomes everyday struggles for the caregivers and those with ASD who are dependent on their caregivers (Simplician, 2015).

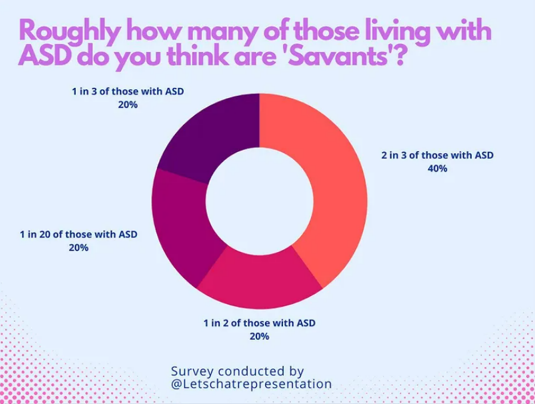

3.3 The Savant & the anti-social

Despite being such a widely represented portrayal of ASD, Savant syndrome only occurs in fewer than one in three people with autism (Howlin, Et al., 2009). Yet, the media has become saturated with portrayals of this very convenient character plot (Nordahl-Hansen, Tøndevold, and Fletcher-Watson, 2018; Nordhal-Hansen, Oien and Fletcher-Watson 2018). ‘Savant syndrome’ itself is in fact another disorder, which can be related to not just ASD but to other developmental disorders as well as those with brain injuries, and so associating it directly with ASD is a misconception that popular media has developed (Treffert, 2009). While more ‘special’ abilities such as hyperfocus or better memory may be attributed to some individuals with ASD, the majority don’t display these in any extraordinary way (Happé, 2018). Parents of those with ASD often are frustrated with how the media portrayals of those with ASD as savants implicate that all the people with ASD are somehow specially talented (Happé, 2018).

Leading through to the other type of ASD representation, often overlapping with the savant stereotype is that of a lack of social skills. This comes in different forms but is often understood to entail the characters with ASD being unable to read the room, understand jokes, communicate effectively with their cohort, or understand politeness and courtesy (Poe and Moseley, 2016). Not only this, but there is also there is also a lack of understanding from the characters around the character with ASD, having no idea and not trying to understand what or how the character with ASD thinks and feels, leading to misunderstandings, comedic effect or simply an awkward moment (Draaisma 2009).

4 Family Values and Culture in South Korea compared to UK/US

4.1 Confucianism & value of family in South Korea

The inclusion of ‘values’ for this dissertation is understood to be ideals, behaviours and concepts that are upheld regardless of situations or events, and so become a universal appreciation of standards within the designated area that these values are held (Hitlin and Piliavin, 2004). SK, much like the rest of the Eastern world, has historically followed the views of Confucianism (Deuchler, 1992). Although there continues to be a shift in this environment as SK has moved more towards a democracy, as well as International influence from being more connected to the outside world, for the purpose of this study, the modernised family views will be considered while appreciating the formation of these values (Lee, 2018, Kim, 2009). There is an emphasis on hierarchy and respect through the ages in SK, where the head of the family will often be its oldest member who is usually male, and community is formed based around the idea of a leader and followers (Śleziak 2013, Kim et al., 2015, Deuchler, 1992). There remains a large placement on young people in SK to work towards the common goal of the state, contributing to the society and invocations requested by the state (Śleziak, 2013). Young people are motivated to achieve by almost a lack of privacy, as their exam results are published publicly, and there would be a degree of exclusion for those who do not achieve socially accepted grades (Śleziak, 2013). The shaming of those who underachieve is a factor in SK society derived from Confucianism, but even after becoming a republic, SK focuses on this as a way in which to control the views and perspectives of the SK people through public shaming of those not upholding the values set out by the government and society (Śleziak, 2013).

4.2 Cultures in the Western world

For the purposes of this dissertation, when talking about Western culture there will be a focus on the US and UK as they represent the biggest International audiences for K-Dramas. There is a focus on individuality and independence within both American and British Cultures, and young people are told to emphasise their individuality (Kim et al., 2013, Baker and Barg, 2019). Though there are differences depending on class status, such as middle-class families being more likely to instruct their children to be more individual, while working class families would influence their children to ‘value conformity and authority’ (Kohn, 1959, 1977 cited in Baker and Barg, 2019). Within the UK especially, there sits a wide variety of culture and dynamics as the UK has gone through a lot of restructuring, including the introductions of new cultures, religions, and societal expressions (Baker and Barg, 2019). In this way, it has been difficult to pinpoint specific values that are unilateral throughout the UK and the wider Western world, as they have benefited from a cross-cultural explosion of unification.

Overall, between both countries there is a more liberal approach towards the values of family, while remaining a family unit, there is a sense of individuality and understanding about each other, as well as ideas of respect moving both ways in the family environment (Kim et al., 2015, Feinberg et al.,2019, Woods, 2018). It is important to note that the usage of liberal is not of the political nature, but it entails minimal authority, policy, or influence from the state over the notions of family in the UK and US (Woods, 2018).

4.3 Culture of Family Comparison

In SK society, ‘togetherness, a clear hierarchy, and harmony among family members are highly valued, whereas independence, individualism, equality, and autonomy are often emphasized in Western cultures’ (Kim, 1997; Kim & Rye,2005 cited in Kim, 2015) While Confucianism and Liberalism seem to be quite different, there are some connecting factors, including that of democracy, though they take different approaches (Ackerly, 2005, He, 2010). In this way an inference to the family values expressed by both cultures can be connected in different ways. While the more liberal countries in the west express more of an individual nature, where each opinion counts, SK views on mutuality, where a people are connected in their views can also be seen in a democratic light, meaning that while their cultures differ, their concepts of expressing opinions and views are tethered (Ackerly, 2005).

Despite both SK and the Western World holding different values in family and culture, Kim et al., (2015) study indicates that differentiation in individuals, as well as family values and family functioning are high in both cultures (Kim et al., 2015). This study therefore indicates that both in SK and the US, the structure of family and the individual, both assert positivity and healthy family relations despite being founded on different principles (Kim et al., 2015). It should also be mentioned that on a wider scale, levels of the parents’ education influences the way their children are brought up, including things like conformity to authority, how hard working they are and independence (Baker and Barg, 2019).

Methodology

Textual Analysis

Firstly, this study will undertake an exploration into whether the case study of It’s Okay to Not be Okay reflects a representation of the theories discussed, while also recognising the shortcomings of the case study. The reason this case study has been chosen as it is not only recent (2020), but it is a popular series among both SK and Western audiences. This dissertation will explore the representation of Moon Sang-Tae as someone with ASD, as well as the relationship between him and his family. By investigating the character of Sang-Tae it can be discerned if the ideology of the content reflects the established research (Bertrand and Hughes, 2018). Such research will explore whether this character and series display authentic representations of ASD and familial relationships and if they reflect cultural status and stereotypes. While this dissertation may be effective as just a textual analysis, without factoring in the wider social context and cultural opinions the case study would not be effective.

Reception Analysis

Several reviews taken from different types of sources such as journalists, Google reviews, Naver and IMDb reviews will forward the second part of this analysis. This way an exploration of audience influence can occur, as media is often curated because of audience influence (Shrøder et al., 2003, Lippman, 1922 cited in Ruddock, 2001). Cultural and reception studies often go hand in hand as culture is often expressed through opinions and reviews throughout media and society (Bertrand and Hughes, 2018). By utilising audience reviews, an expression of the thoughts on the representations displayed within the series can be ascertained, to suggest whether audiences view the series as exhibiting realistic or stereotyped versions of ASD.

This follows on from the theories that the ways in which disability, predominantly intellectual disability, are viewed differently across cultures. A collation of responses signifies the opinions of the audience on this representation of ASD and the dynamics of those around Sang-Tae. While the sample size is low, it represents wider sentiments. This way a cross cultural comparison can be drawn to recognise features of the respective television audiences. It is important to discuss overall opinions of the K-Drama also, as even if the designated representations are well presented, if the case study itself is not well liked, it will have reluctant viewership.

For translation of SK language articles, translation software Google Translate will be used, along with the help of an SK national, who will also provide some cultural perspective on elements of this dissertation from the perspective of a SK citizen. This person will be referred to as K, as they would rather keep their identity private. In some cases, translation errors occurred, and so Gang-Tae may sometimes be called Kang-Tae, as well as genders being altered but this was acknowledged throughout translation.

Data collection

Eleven reviews from SK media, and the same number of reviews from UK/US sources will be analysed after being narrowed down from a wide pool to ensure a wide range of opinions are found, but there is not a repeating of opinions. Bertrand and Hughes (2018) infer that sample sizing can have a direct correlation with how accurate or in-accurate a study might be. An investigation into the differences or similarities of opinions will be conducted.

Evaluation of methods

Utilising a more textual analysis to confer if the case study fits into a category of accurate representation hinges on given literature being reflective of the current environment and experience of those with ASD. While there has been extensive research into such topics and this dissertation has pulled on a lot of them, it should be noted that there is a constant shift in the environment and understanding of ASD, its symptomatic expression and the family and societal connections involved. Identity can be difficult to trace by using the internet, but including official publications ensures that as much as possible the target audience is met (Wimmer and Dominick, 2011, Bertrand and Hughes, 2018).

Analysis

Textual Analysis

ASD representation in the form of Moon Sang-Tae

We are told that Moon Sang-Tae has asperges by his brothers’ interactions with their friends and strangers. While being 35 at the start of the series, Sang-Tae often displays characteristics unlike his age, such as an avid interest in children’s fairy-tale books, as well as dinosaurs. This, along with his struggling social skills inability to understand the wider world around him, creates a picture of the realisms of ASD from a learning perspective (Prior, and Kyrios, 2007, Worley and Matson, 2012).

The mannerisms and symptomatic expression that Sang-Tae displays throughout the course of the series may be understood as ASD, as he displays a lot of the symptoms that ASD is associated with, such as a lack of social skills, self-destructive behaviour, repetitive play, flapping and aggression (Matson et al., 2011, Lotter, 1980, Mandall and Novak, 2005). When looking at this symptomatic expression through the lens of a cultural representation, Sang-Tae does demonstrate a better understanding of being able to read the room, understand age-appropriate jokes, and language (Matson et al., 2011, Mandall and Novak 2005, Scarborough, and Poon, 2004). This in some ways concurs with the findings of the research from a cultural perspective as those in SK who have ASD show greater understanding of social skills and the aforementioned skills, but Sang-Tae also demonstrates some tendencies that are associated closer with the UK and US symptomatic expressions, this being aggression and challenging behaviours (Matson et al., 2011, Mandall and Novak, 2005). The reasonings behind this can only be speculated and would need further investigation into the production of the series.

The characters within It’s Okay to Not be Okay show a strong opposition to the usual cultural environment in SK, that being a resistance and lack of understanding about ASD, and instead sought to understand Sang-Tae as well as help his brother in the caregiver role (Matson et al., 2011). Throughout the series, we see many characters, some friends of Gang-Tae, or people who have gotten to know the brothers along the way, undertake a caregiving role for Sang-Tae when needed and being accepting of his ASD which is something unexpected when referring to the literature uncovered by the earlier research, as SK has a high resistance to not only diagnosis of ASD, but the management of this condition as anything else but being deficient (Matson et al., 2011, Mandall and Novak, 2005).

One could argue that the inclusion of Sang-Tae being a brilliant illustrator as the Savant trope being imagined like it has in so many other media but Sang-Tae himself makes a comment on this, saying that “I was born with the talent. It’s a natural born talent”. At no point in the series either, is it assumed by characters in the series that because Sang-Tae has ASD, that he should be skilled in any particular manner (Draaisma, 2009). Sang-Tae also displays memorization skills, but these are mainly displayed when he is watching his favourite TV program, wherein he recites the lines word for word. While this could be attributed to Savant syndrome it’s important to understand that repetitive behaviours are a part of ASD, and so if Sang-Tae has watched this cartoon numerous times it would be understandable that he has memorized the lines (Zandt, Prior and Kyrios, 2007). During the series though, Sang-Tae shows growth in his social skills, becoming less anti-social as well as the characters around him coming to understand him and communicate with him as best as they can, which is often omitted in representations of ASD, and replaced with comedic moments or ignorance for their different ways of thinking (Draaisma 2009, Poe and Moseley, 2016).

Family dynamics surrounding Moon Sang-Tae

We are introduced to Sang-Tae as his brother Gang-Tae must attempt to calm the director of the vocational school Sang-Tae goes to, as Sang-Tae has caused trouble at the school. We see that he is remorseful but can’t voice his concerns, other than commenting that he knows when his brother Gang-Tae is angry by looking at his facial expressions. While Gang-Tae doesn’t let his brother know, he is deeply frustrated by always having to look after his brother and live his life for his brother. The reality of sibling relationships under stress due to the inclusion of disability is portrayed much like how Mclaughlin et al., (2008) investigated.

There is a turning point however, as Gang-Tae begins to stand up to his brother and vent his frustrations. At first this comes out as clumsy and usually escalates to a physical fight as this clip demonstrates. These siblings, as they grow into adulthood may also become more disconnected and more pessimistic about the future, which Gang-Tae is as he struggles with having to adjust to continually moving because of his brother’s nightmares (Orsmond and Seltzer, 2007). While sometimes subtle, Gang-Tae begins to open-up and express himself more as his relationship with Ko Mun-Yeong (Seo Yea-Ji) develops, allowing him to have a better outlook of the future, but also a better relationship with his brother. The empathy and kindness showed by Gang-Tae throughout the series towards the patients of OK psychiatric hospital can be seen in parallel to the kindness and understanding he has shown to his brother, exemplifying the research done for real world equivalents of this type of relationship (Mclaughlin et al., 2008, Hodapp et al., 2010, Orsmond and Seltzer, 2007).

Most notably, Gang-Tae struggles with the pressure of having to grow up quickly to take care of his disabled sibling, had to compensate for him and had no time for himself which Naylor and Prescott (2004) comment is a large part of the realities of having a disabled sibling. While their mother seems to have the best intentions, at times she has told Gang-Tae that he exists only for Sang-Tae, once again forcing the role of caregiver onto him, and leading to the memory of his mother Gang-Tae has in this clip (Allen, 2017, Kittay, 2001, Simplican, 2015). But, as Sang-Tae and Gang-Tae’s mother dies early on in their lives, a decisive answer to this drama’s representations in reference to the relationship Sang-Tae holds with his mother is inconclusive (Peterson, 2006 cited in Allen, 2017).

Throughout the series, there is a theme of ‘belonging’ not only in the sense of having somewhere to belong, but also belonging to someone. The brothers’ relationship, through themselves is expressed as belonging to Sang-Tae. There are arguments throughout the series where Sang-Tae is starting to make his own decisions, but Gang-Tae struggles to accept that Sang-Tae knows what’s best for himself. By the end of the series, we see another shift in the relationship between Sang-Tae and Gang-Tae, as Sang-Tae begins to understand that his brother does not belong only to him. There were times where, in Sang-Tae’s own way of expressing he proclaimed Gang-Tae as his “Moon Gang-Tae belongs to Moon Sang-Tae” but, as the series final arc begins to settle, Sang-Tae tells his brother that “Moon Gang-Tae belongs to Moon Gang-Tae”, and it is seen as the acceptance from both brothers that they belong to themselves, and are not controlled by each other. This is a pivotal turning point, as the brothers now are able to rest easy and live their own lives rather than simply relying on each other; a positive ending and new beginning for the relationship between the brothers which sees the caregiver role forced upon Gang-Tae released, and with it the sibling burden placed on him, so he can explore the country with Ko Mun-Yeong, something that a lot of real life people with a disabled sibling feel that they cannot do as they are pressured into burdens of care (Wolf, et al., 1998 cited in Naylor and Prescott, 2004).

It seems decisively, in the field of the portrayal of a realistic sibling relationship wherein one of the siblings are disabled or impaired, It’s Okay to Not be Okay follows the trend which was uncovered by research done into these relationships (Mclaughlin et al., 2008, Naylor and Prescott, 2004, Orsmond and Seltzer, 2007).

Reception Analysis

Overall reviews, positive and negative sentiments

South Korea

Overall, the reviews from SK are positive, but there is a lot of discourse around some of the actors within the series, as there was controversy surrounding the female lead. Unfortunately, therefore it cannot be allocated that negative reviews are exclusive or inclusive of the story and characters of the K-Drama itself, so when talking about negative reviews this dissertation will attempt to clarify this by using the reviews themselves as evidence for a reflection of the opinions, rather than any scoring or rating. Negative reviews commented that they were unable to relate to the characters within the series as they displayed characteristics unlike that of real life (Article 5a).

The series was commended for having good chemistry between the main characters, inclusive of Sang-Tae, becoming a ‘family unit’ through the series (Article 1a, 4a, 7a, 9a, 11a). Family values, as discussed in the literature review, are an important part of SK culture. While there is a romantic plot unfolding between the two leads, audiences infer that Moon Sang-Tae has his own story of love as he accepts Ko Mun-Yeong into the family and they become a family unit, accompanying traditional SK views on family (Article 1a, 4a, 7a, 8a, 9a, Śleziak, 2013, Kim et al., 2015).

International

A more diverse range of reviews were used for the International reviews, as different platforms reflect different audiences as well as access to these platforms. Overall, reviews were positive, and the reviews commend the series for its positive representations of mental health in a realistic manner (Article 1b, 2b, 3b, 4b). Some reviews also mentioned that the series became educational for them, teaching them about mental health and how it can affect people, as well as the realism in the healing process (Article 3b, 4b, 7b, 8b, 9b, 11b).

There were contrasting thoughts on the series’ use of a fairy-tale lens to approach the storytelling, many International reviewers found that it hindered the story by making it less realistic, less relatable, and even introducing some inconsistencies (Article 5b, 10b). The largest part of this that reviews comment on is the mother’s arc, concluding with Ko Mun-Yeong’s mother returning and being thwarted by the three leads, as being unrealistic and not well explained (Article 1b, 5b, 8b, 10b). There were also reviews that held a more positive regard for the fairy-tale lens, as it allowed audiences step back from the often-dark drama and see it from a lighter perspective, as well as allowing for more simplistic explanations for how characters feel, since some characters throughout the series show restraint in expressing themselves (Article 1b, 7b, 9b, 11b).

Another mentionable reaction was the dismay in the female lead, as some reviewers believed that the mental illness displayed by the female lead was not an excuse for acting like a ‘sicko’ or ‘bitch’ throughout the series (Article 5b, 6b, 10b). While this view ascertained a minority, a useful comment in a review believes that if the gender roles were reversed, there would have been an explosion of negative reviews as it would be a male assaulting a female rather than vice versa (Article 5b). Though, most other reviews in the sample disagree, saying that the character of Ko Mun-Yeong has a lot of development throughout the series, and heals from her trauma and begins to move on (Article 1b, 7b, 8b)

Comparison

Both SK viewers and International viewers overall liked the series. Though there were some outliers, with important points on the actions of certain characters, as well as disappointment in the series for its fairy-tale lens. Within the debate of the fairy-tale lens, International audiences disliked it much more than SK audiences, which seems to stem from the unrealistic approach it offers. It could be said that it is due to K-Dramas utilising a more unrealistic formula for its audiences; Lin (2019) approaches this as a reflection of SK society wanting to be swept off their feet by romance dramas that may include many tropes and stereotypes (Lin, 2019). If so, SK audiences would be more accepting of these trope filled dramas than International viewers who have less access to these K-Dramas.

It is also worth mentioning the discrepancies that SK and International audiences had over the female lead. While SK viewers were more sympathetic to the female lead Ko -Moon-Young even if they could not relate to her, many International viewers had less sympathetic views, calling her toxic (Article 1a, 4a, 5a, 7a, 8a, 9a, 5b, 6b, 10b) A conclusion cannot be drawn whether this is inherently cultural, but speculation can be made that due to the changing environment in SK as it continues its democratic learning, there may be restraint in communication of negative ideas as a result of previous Confucianism views, rather than the more liberal and ‘free speech’ driven west (Deuchler , 1992, Lee, 2018, Kim,, 2009, Śleziak, 2013).

Reactions to the representations of ASD and family culture

South Korea

As the sample of reviews reflects overall opinions without too much duplication, noticeably absent are mentions of ASD and its place in the K-Drama. Most SK reviews do not mention ASD specifically, they opt for praising the actor Oh Jung-Se who plays Moon Sang-Tae and comment on his effectiveness in the role (Article 1a, 8a, 9a). It could be ascertained that due to cultural resistance, there was less of a push to comment about the ASD representations in this K-Drama as in SK culture, even parents of those with ASD may reject and deny any identification or treatment and we could be seeing this ‘out of sight out of mind’ kind of reflection through a lack of mention in the reviews (Grinker and Cho, 2013, Matson et al., 2011, Mandall and Novak, 2005). This cultural resistance appears to stem from the almost formulaic beliefs that are part of Confucianism ideals and the endeavours of parents and families to seem not only as normal as possible, but to be highly achieved and make the family proud (Śleziak, 2013, Kim et al., 2015). Though this could also stem from the angle that the character of Sang-Tae developed and grew and got a happy ending, despite ASD, as we see that others throughout the series develop and grow despite their mental afflictions (Article 1a, 4a, 7a).

There are however some reviews that do mention ASD (Article 2a, 3a, 8a, 10a, 11a). The ratio of SK reviews that mention ASD has remained even when a wider range of articles were considered, which means that the selected articles containing this ASD representation are a conglomeration of reviews in which SK audiences directly mention ASD. While some of these representative reviews come from disability or ASD related blogs, they relay the same understanding, and were also some of the only blogs found to openly communicate the accuracy or appreciation of the ASD representation in the case study (Article 2a, 3a). Although one such article comments on the misrepresentation of characteristics of ASD, it boiled down to thoughts on how ASD effects certain individuals, and the series was criticised by including certain lines of dialogue like ‘’I think the back of my head is sensitive. Is that the erogenous zone?’’ (Article 3a). This dialogue, while criticised, represents a misunderstanding of ASD, but even the author of this post reflects that the K-Drama attempts to show a wider awareness for such conditions, and should be commended for such (Article 3a). Though there has been research into ASD and Erogenous zones, concluding that some with ASD may have hypersensitivity of these zones (Griffioen, 2021)

Within these articles, the ASD representation was seen as positive and has provided a good medium to be educational to wider audiences who may not have known or understood the disorder; as well as offering a realistic and dynamic approach to understanding ASD (Article 8a, 10a, 11a) One review calls out a specific comedy scene including Ko Mun-Yeong and Sang-Tae, wherein Sang-Tae is his honest self and comments on Ko Mun-Yeong’s hair, causing her to retort back at him; Ko Mun-Yeong does not treat Sang-Tae any differently and is still her same self (Article 10a). Another article mentions a scene that happened earlier on in the drama, where a misunderstanding occurs because Sang-Tae approaches a young girl wearing dinosaur clothing, and as Sang-Tae loves dinosaurs he attempted in his own way to communicate with the girl, which ended up causing a concerning scene for everyone (Article 11a).The author of this article compares symptoms of ASD also discussed in this dissertation, offering a comparison to the K-Drama and the understanding that Sang-Tae resides in an accurately represented form of ASD (Article 11a).This article also discusses other parts of ASD in relation to the series, calling out how characters are recognised and accepted for their disabilities, and are allowed to shine (Article 11a). This, and the other articles hope that this K-Drama offers up a chance for more realistic representations and awareness of those with ASD and other mental or developmental disorders (Article 3a, 8a, 10a, 11a).

Within these articles that mention ASD representation, some also make mention to the characteristics of the Savant syndrome that Sang-Tae displays (Article 10a, 11a). While discussed in the textual analysis, Sang-Tae’s memorization skills and ability to paint can be inferred to be either because of ASD like these reviews state, or abilities that he has as well as ASD (Article 10a, 11a). Despite this, it is important to mention these reviews as it establishes the understanding that audiences have of ASD, and perhaps aligns itself with the representations of Savant syndrome previously seen in media and TV (Nordahl-Hansen, Tøndevold, and Fletcher-Watson, 2018, Nordahl-Hansen, Oien and Fletcher-Watson, 2018).

There is also an emphasis on the sibling relationship within this drama, running parallel with the mentions of family, further enforcing the importance of family in SK culture (Article 1a, 4A). While it is not expressly mentioned in the representative reviews, the discussion of a ‘happy ending’ for all the characters comes from the found freedom that the brothers find after having to rely on each other (Article 1a, McLaughlin et al., 2008, Orsmond and Seltzer 2007). Reviews also mention the journey of expression between the brothers as they learn to communicate with each other and become empathetic to each other and contained many ‘heart-warming’ moments for audiences (Article 4a, 7a, 8a, McLaughlin et al., 2008, Hodapp et al., 2010,).

International

There were more reviews Internationally that spoke directly about the representation of ASD within the K-Drama and spoke about the positivity and sense of connection it created as some reviewers compared it to friends or family around them who have ASD (Article 1b, 2b, 3b, 4b, 6b, 7b, 8b, 10b, 11b). These reviews also make mention to a scene that happens early in the drama, wherein we see the world from Sang-Tae’s perspective and how it was incredibly insightful for International audiences to take a step into their world (Article 1b, 10b).

More International audiences feel that they can sympathise and understand the character of Sang-Tae, as well as Gang-Tae as his caregiver (Article 2b, 3b, 6b, 7b). These reviewers who compare it to real life scenarios of their own experiences in these caregiver roles have expressed the accuracy and realistic manner that the ASD representation as well as the responsibilities of the caregiver and sibling relationships hold for them (Article 2b, 3b). Even reviews that do not expressly talk about their real live experiences, call for praise as they believe the topics of both mental health and ASD were displayed honestly and educationally (Article 4b, 6b, 8b). One reviewer, although giving a negative review for the series, commented that the only reason they continued to watch the drama was for Sang-Tae and the accurate and tear inducing portrayal of ASD (Article 6b).

It is important to note one of the reviews specifically talks about their own son with ASD, and how the series has provided them with informative examples, with some being negative (Article 3b). This is also greatly important, as the show does have moments as discussed previously where a toxic or unkind relationship or scenario happens, and this review has expressed that they understand that not only does the case study display excellent and educational understandings of ASD, but also has been shown in a manner almost to avoid at times, demonstrating the wide variety of representation for ASD and the caregiver role associated (Article 3b, 9b, Kittay 2001, Simplican, 2015).

International audiences’ reason that the development of Sang-Tae throughout the series, going from “Moon Gang-Tae belongs to Moon Sang-Tae” to “Moon Gang-Tae belongs to Moon Gang-Tae” as one of the pinnacles of the series (Article 7b, 8b). Throughout the series, he was seen to be an integral part, and having someone with ASD as part of the main cast has resonated well with International audiences who became attached to Sang-Tae and his found family (Article 1b, 7b, 8b, 9b, 10b, 11b). Sang-Tae’s development over the series, expressly not in a manner to cure his ASD by the end of the series, but to adjust to a changing environment and come to love his new family and be independent is a highlight for many International viewers, who found it heart-warming and tear jerking to watch Sang-Tae develop (Article 1b, 4b, 7b, 8b, 9b, 10b, 11b).

There are mentions to family, and how the trio become a ‘true family’ through the events of the series, as well as how realistic the interpretation of the caregiver role put upon Gang-Tae throughout the early parts of the series is ( Article 1b, 2b, 4b, 6b).This view on sibling relationships, especially those with a disabled sibling, matches with the research and confirms the realism in the representation of the positives and negative of sibling relationships in this K-Drama (Article 1b, 2b, 6b, Orsmond and Seltzer, 2007, McLaughlin et al., 2008,) It should also be mentioned that some International reviews included dismay for Gang-Tae being stuck to Sang-Tae and forced to take care of him (Article 1b, 6b). Despite holding more liberal views in terms of family values, audiences reacted well to the ‘wholesome’ depiction of siblings transforming into a family trio (Article 1b, 4b, Kim et al., 2015, Feinberg et al., 2019, Woods, 2018)

Comparison

There is different consideration given to the family values discussed in both SK and International reviews. While both make mention to the ‘wholesome’ family unit made up of the three leads, it is important to understand from a cultural standpoint that their appreciations come from different angles; SK being a more traditionally focused, family above all else, while more liberal views are expressed by International audiences (Śleziak, 2013, Kim et al., 2015, Feinberg et al.,2019). Regarding this, International audiences have expressed a concern for Gang-Tae as towards the beginning of the series he is very much bound by Sang-Tae; creating what International audiences feel is not a healthy relationship; which is reflected in the literature discussed (Begum and Bachler, 2011, Orsmond and Seltzer, 2007). In the International reviews, there is more of a focus and appreciation on the care and consideration that Gang-Tae gives to Sang-Tae, and how he gives up a lot for his big brother and is held down by him, while learning to let go during the series (Article 1b, Article 2b, Article 6b, Article 7b, Article 11b, McLaughlin et al., 2008, Orsmond and Seltzer, 2007) This discussion was not apparent in the SK reviews , and there was little mention to the burden of care (Article 4a). While definitively, a conclusion cannot be drawn as to why SK reviews were less likely to talk about the responsibility of care that the siblings endure, it could once again lead back to notions of family, where there is more of a pressure to perform family roles in SK, leading to this duty of care to be a given, not something that Gang-Tae is actively doing because of his love for his brother (Mandall and Novak, 2005, Lee, 2018, Kim et al., 2015, Nixon and Cummings, 1999).

Compared to SK reviewers, International reviewers were much more open and expressive of how they spoke about the representations of ASD in the K-Drama. Many SK reviews only opted to talk about the actor accurately portraying Sang-Tae, rather than discuss the accuracy or inaccuracy of the representation (Article 1a, 8a, 9a). It was discussed that this could be due to cultural resistance, and this may be even more likely as we see a lot of International reviews discuss their thoughts and feelings on the portrayal of ASD within the drama (Article 1b, 2b, 3b, 4b, 6b, 7b, 8b, 10b, 11b). While it cannot be concluded that the reason behind this disparity is due to cultural differences it can be inferred and through the literature discussed it seems the most likely scenario; with SK’s more conservative views leading to less of a discussion on representations of disability compared to more liberal views Internationally (Grinker and Cho, 2013, Matson et al., 2011, Mandall and Novak, 2005, Baker and Barg, 2019).

Delving into the reviews that do talk about the representations of ASD in the case study, both SK and International audiences believed it was accurate and educational, many SK reviews simply talked about it on the surface, and only two of them talked about wider views and information on ASD (Article 2a, 10a). International reviews often decided to go into greater detail, some mentioning their own experiences surrounding ASD and creating more of a relatability to the characters, as well as expressing their love for the character and his development throughout the series (Article 1b, 3b, 4b, 7b, 8b, 9b, 10b, 11b). In SK, disability is often discriminated against, and anything derived from the normal Confucianism family values becomes a struggle against the tide (Śleziak 2013, Park, 2017). Although we do see this environment shifting as SK continues to learn as a Republic, perhaps there is still a way to go for these kinds of representations to be talked about and expressed as freely as International audiences do.

It is interesting to discuss also, that some SK reviews who do mention ASD, also mention Savant syndrome, which occurs in fewer than one in three people with ASD, and how the character of Sang-Tae shows these characteristics (Article 10a, 11a, Howlin et al., 2009). What is increasingly interesting however, is that International audiences did not mention this in their reviews. While in this dissertation it has argued both ways that Sang-Tae does or does not display Savant syndrome, could this be SK attempt to open up dialogue about these types of skills? During research of Savant syndrome, it was uncovered that parents of those with ASD had often become frustrated with media portrayals of those with ASD having Savant syndrome, as it implicated that all people with ASD had special talent (Happé, 2018). With SK’s competitive environment, and the fact that SK takes part in the public shaming of those not upholding the values set out by the government and society, could this be their way of attempting to justify expressions of ASD, by entailing it as something expressly positive, and not something that debilitates or restricts those with ASD (Śleziak 2013)? It is important to note that these practices do not happen all over SK, especially as it shifts and learns from International cultures, but often students’ exam results are displayed publicly, as well as class averages, leading to a more competitive environment growing up (Śleziak, 2013).

From an interview with K about this, they discussed that from their experience rather than SK being against disability, they don’t talk about it much because they just want to treat them as ‘normal people’. K recounts a time when they were in school and had a physically disabled classmate, and how they and their friends interacted with this person without restraints due to their disability. As K is a young person in SK, this could reflect a more optimistic approach with younger generations, as age was not considered during debates about disability, discrimination, and opinions on the case study. Perhaps an avenue of future research would be any possible link to viewership, age and identity embedded within a similar case study surrounding disability. In terms of role and rule resistance for SK, K comments that from their experience it’s half and half when it comes to upholding values set out by society. They mention that there is a lot of expression within their culture, which may be to do with the shifting environment within SK to a much more democratic and open view. Despite this, literature and experience still entail SK to be quite conservative in certain ways, including expressions of disability.

Conclusion

From a coalition of both a textual analysis and reception analysis, this dissertation set out to identify the intent, accuracy and understanding of ASD as well as the family values and roles situated around it as it is represented in TV, using the case study of a Korean drama It’s Okay to Not Be Okay (2020).

The textual analysis identified areas in which accurate ASD representation was found, including in the symptomatic expression of the character Moon Sang-Tae and how he interacted with the world around him and the pivotal development he underwent. Gang-Tae’s role as a caregiver to Sang-Tae expresses the explored literature on sibling relationships with disabilities, and encapsulates research into sibling relationships, as well as the understanding of both the positive and negative connotations such as empathy and understanding, arguments and frustration and learning to understand each other (Hodapp et al., 2010, Orsmond and Seltzer, 2007. Mclaughlin et al., 2008). Therefore, this case study contains a progressive and modernised representation of ASD and family relationships surrounding it.

The reception analysis identified key differences in SK audience and International audience understanding and appreciation of ASD, and its representations in TV. SK reviewers were less likely to talk about ASD, instead opting to talk about the effectiveness of the actor. When they did speak about it, their focus was either on raising awareness for ASD and related conditions or discussing Savant syndrome. As discussed, this seems to come from a cultural understanding that these things should go unsaid, as well as a cultural resistance to the diagnosis and understanding of ASD. The South Korean citizen who was interviewed during the dissertation commented that in their opinion it was the former, that these kinds of things would go unsaid as to not raise the question of making people with ASD feel different or anything but ‘normal’. The role of the caregiver Gang-Tae was briefly discussed, but the reviewers focused more on the notions of a family between the three main characters and how they each helped one another.

International reviewers were more open to discuss the relevant representation of ASD, and some even discussed personal experiences with ASD. An important mention for International viewers was the development of Sang-Tae throughout the series, becoming more independent and understanding others better. As cultural differences were a main theme in this dissertation, the reasoning behind these differences can be said to be the difference in cultural values, between family culture and disability culture (Grinker and Cho, 2013, Matson et al., 2011, Mandall and Novak, 2005, Baker and Barg, 2019).

References

Ackerly, B. A., (2005) ‘Is Liberalism the Only Way toward Democracy? Confucianism and Democracy’ Political Theory, 33(4) pp.547-576.

Allen, H. (2017). Bad mothers and monstrous sons: Autistic adults, lifelong dependency, and sensationalized narratives of care. Journal of Medical Humanities, 38(1), pp.63–75.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-text revision (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author

Baker, W., Barg, K., (2019) ‘Parental values in the UK’ The British Journal of Sociology,70(5), pp.2092-2115

Begum, G., and Blacher, J., (2011) ‘The Sibling Relationship of Adolescents with and without Intellectual Disabilities’ Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(5), pp.1580-1588

Bertrand, I., Hughes, P. (2018) Media Research Methods, London: Palgrave

CDC (2021) autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/index.html (Accessed November 4th, 2021).

Chung, K., Jung, W., Yang, J., Ben-Itzchak, E., Zachor, D. A., Furniss, F., Heyes, K., Matson, J. L., Kozlowski, A. M., Barker, A. A., (2012) ‘Cross cultural differences in challenging behaviours of children with autism spectrum disorders: An international examination between Israel, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America’ Research in Autism Spectrum Disorder, 6(2), pp.881-889.

Daley, T. C., (2002) ‘The Need for Cross-Cultural Research on the Pervasive Developmental Disorders’ Transcultural Psychiatry, 39(4), pp. 531-550

Dean, M., Nordahl-Hansen, A., (2021) ‘A Review of Research Studying Film and Television Representations of ASD’ Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Published Online.

Deuchler, M., (1992) The Confucian transformation of Korea: A study of Society and Ideology. Asia Centre: Harvard University Press

Draaisma, D. (2009) ‘Stereotypes of autism’, Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society Biological sciences, 364(1522), pp.1475–1480.

Feinberg, M., Wehling, E., Chung, J. M., Saslow, L. R., Melvær Paulin, I., (2019) ‘Measuring moral politics: How strict and nurturant family values explain individual differences in conservatism, liberalism, and the political middle’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(4), pp.777-804.

Griffioen, T., (2020) ‘Autism Spectrum Disorders’ Psychiatry and Sexual Medicine, pp.341-352.

Grinker, R. R., Cho, K., (2013) ‘Border Children: interpreting Autism Spectrum Disorder in South Korea’ Journal of the Society for Psychological Anthropology, 41(1), pp.46-74

Happé, F., (2018) ‘Why are savant skills and special talents associated with Autism?’ World Psychiatry, 17(3), pp.280-281.

He, B., (2010) ‘Four models of the relationship between Confucianism and democracy’ Journal of Chinese Philosophy,37(1), pp.18-33.

Hitlin, S. and Piliavin, S. (2004) ‘Values: Reviving a Dormant Concept’, Annual Review of Sociology 30(1), pp.359-393

Hodapp, R. M., Urbano, R. C., Burke, M. M. (2010) ‘Adult Female and Male Siblings of Persons with Disabilities: Findings from a National Survey’ Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 48(1), pp.52-62.

Honey, E., Leekam, S., Turner, M., McConachie, H., (2007) ‘Repetitive Behaviour and Play in Typically Developing Children and Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders’ Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(6), pp.1107-1115.

Howlin, P., Goode, S., Hutton, J., & Rutter, M. (2009) ‘Savant skills in autism: psychometric approaches and parental reports.’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 364(1522), pp.1359–1367.

Kim T. (2009) ‘Confucianism, Modernities and Knowledge: China, South Korea and Japan.’ International Handbook of Comparative Education. 22, pp.857-872

Kim, H., Prouty, A. M., Smith, D. B., Ko, M., Wetchlet, J. L., Oh, J., (2015) ‘Differentiation and Healthy Family Functioning of Koreans in South Korea, South Koreans in the United States, and White Americans’ Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 41(1), pp.72-85

Kim, U. S., Leventhal, B. L., Koh, Y., Fombonne, E., Laska, E., Lim, E., Cheon K., Kim, S., Kim, Y., Lee, H., Song, D., Grinker, R. R., (2011) ‘Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder in a Total Population Sample’ American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(9), pp.904-912.

Kittay, Eva Feder. (1999) Love's Labor: Essays on Women, Equality and Dependency. New York: Routledge.

Lee, D., (2018) ‘The evolution of family policy in South Korea: from Confucian familism to neo-familism’ Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 12(1), pp.46-53

Lin, W., (2019) ‘Reconsidering love in Japanese and Korean trendy dramas’ Tamkang Review, 50(1), pp.113-119.

Lotter, V. (1980) ‘Cross Cultural Perspectives on Childhood Autism’ Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 26, pp.131-133.

Mandall, D., S., and Novak, M. (2005) ‘The role of culture in families’ treatment decisions for children with autism spectrum disorders’ Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 11(2), pp. 110-115.

Matson, J. L., Worley, J. A., Fodstad, J. C., Chung, K. M., Suh, D., Jhin, H. K., Ben-Itzchak, E., Zahor, D. A., and Furniss, F., (2011) ‘A multinational study examining the cross-cultural differences in reported symptoms of autism spectrum disorders: Israel, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America’ Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(4), pp. 1598-1604

McLaughlin, J., Goodley, D., Clavering, E., Fisher, P., (2008) Families Raising Disabled Children London: Palgrave Macmillan,

Naylor, A., Prescott, P., (2004) ‘Invisible children? The need for support groups for siblings of disabled children’ British Journal of Special Education, 31(4), pp.199-206.

NHS (2021) Conditions: Autism. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/autism/ (Accessed November 4th, 2021).

Nixon, C. L, Cummings, E. M., (1999) ‘Sibling Disability and Children’s reactivity to conflicts involving family members’ Journal of Family Psychology, 13(2), pp.274-285.

Nordahl-Hansen, A., Oien, R. A., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2018a). Pros and cons of character portrayals of autism on TV and Film. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(2), pp.635–636.

Nordahl-Hansen, A., Tøndevold, M., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2018). ‘Mental health on screen: A DSM-5 dissection of portrayals of autism spectrum disorders in film and TV’. Psychiatry Research, 262, pp.351-353.

Orsmond, G. I., and Seltzer, M. M., (2007) ‘Siblings of individuals with autism or Down syndrome: effects on adult lives’ Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(9), pp.682-696.

Park, J. Y. 017) ‘Disability discrimination in South Korea: routine and everyday aggressions toward disabled people’, Disability & Society, 32(6), pp.918-922.

Poe, P., Moseley, M. C., (2016) ‘"She’s a little different": Autism-Spectrum Disorders in Primetime TV Dramas.’ ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 73(4), pp.291-313.

Ruddock, A., (2001) Understanding Audiences, London: Sage Publications.

Ruddock, A., (2007) Investigating Audiences, London: Sage Publications.

Scarborough, A. A., & Poon, K. K., (2004). The Ecological Context of Challenging Behaviour in Young Children with Developmental Disabilities. International review of research in mental retardation, 29, pp. 229–260.

Shrøder, K., Drotner, K., Kline, S., Murray, C., (2003) Researching Audiences, London: Arnold.

Simplican, S.C., (2015) ‘Care, disability, and violence: Theorizing complex dependency in Eva Kittay and Judith Butler’. Hypatia, 30(1), pp.217-233.

Śleziak, T., (2013) ‘The role of Confucianism in contemporary South Korean society.’ Rocznik orientalistyczny, 1, pp.27-46.

Treffert, D. A., (2009) ‘The Savant Syndrome: An Extraordinary Condition. A Synopsis: Past, Present, Future’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 364(1522), pp.1351-1357

Troyb, E., Knoch, K., Barton, M., (2011) Phenomenology of ASD Definition, Syndromes, and Major Features USA: Oxford university Press

United States Department of Education (2002). Twenty-third annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC:

Wimmer, R. D., and Dominick, J. R., (2011) Mass Media Research: An Introduction Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

Woods, D.R. (2018). ‘The UK and the US: Liberal models despite family policy expansion?’ Handbook of Child and Family Policy, pp. 182-194

Worley, J. A., Matson, J. L., (2012) ‘Comparing symptoms of autism spectrum disorder using the current DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria and the proposed DSM-V diagnostic criteria’ Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), pp.965-970.

Zandt, F., Prior, M. and Kyrios, M., (2007) ‘Repetitive behaviour in children with high functioning autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder’ Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 37(2), pp.251-259.

Appendix

To read all of the online articles mentioned throughout this work, please download this file.

.

Comments