DOI: https://doi.org/10.33008/IJCMR.2022.02 | Issue 8 | May 2022

Robert Harrison (Bath Spa University)

This work is one of two 2022 winners of our Centre for Media Research Student Award, a special prize awarded to a Media Communications student each year whose dissertation research shows exemplary quality, scope and ambition, and which has also been creatively reimagined to engage and benefit a wider industry audience. The winner of the Student Award is invited to publish their dissertation research alongside their accompanying creative project, and this work is presented at our annual Degree Showcase event.

Abstract

A screenshot into the world. That’s all the film poster allows an audience, showing the fine balance between constructing meaning and grabbing audience attention. This balance is

explored throughout this research, which used the case study of Star Wars and took the form of two stages. On an academic level, it looked into how changes within the industry have resulted in two main variables of alteration, artistic style and composition for today's film posters, resulting in trends and stages of similarities across the traditional and contemporary promotional film landscape. Specifically, this research found that contemporary film posters have become formulaic with film and marketing industries using the same composition (what I term the 'celebrity pyramid') and art style (real images photoshopped) within the large majority of their posters, using the case study of Star Wars to study this change. I argue that this has resulted in audiences becoming less engaged with posters and many wanting posters to go back to the traditional style from the 1970s.

On a second level, and going beyond an academic dissertation, this research undertook industry research into the marketing sector in order to develop the conclusions from the research into a practical and creative set of digital media artefacts beneficial to industry. Specifically, this project aimed to recreate the Star Wars sequel trilogy posters, which many fans saw as uninspired, using the style of traditional posters such as the original Star Wars trilogy. As well as this, I then aimed to explore how this can be pushed into contemporary society, adding moving elements to the posters which would make them stand out. In doing so, and with my academic conclusions asking the question of whether nostalgia impacts the success of posters, with ‘old school’ artwork and style having and greater positive result, this work explores a possible outlet for industry to develop a new trend of film posters, harnessing the possibilities that digital technology and social media have given us.

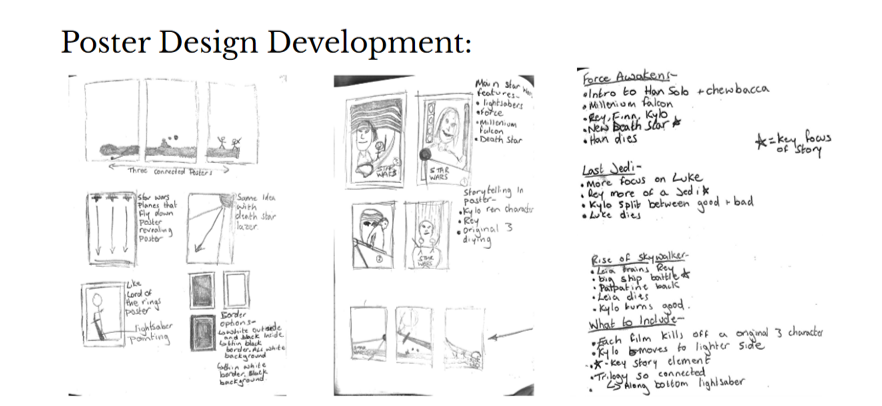

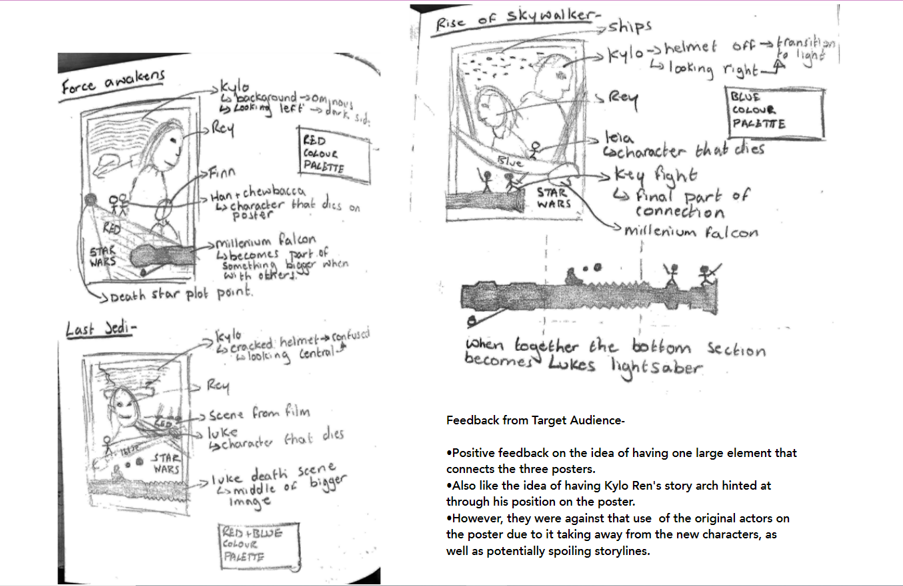

Below I include sample documentation of the poster design research as well as the posters themselves. The full creative work can be viewed online here. Beneath the documentation work and the digital posters you will find the complete academic dissertation in full.

Introduction

“I feel a great disturbance in the force”, or maybe it’s just stagnation? Ever since we have entered Web 2.0 and the contemporary film industry, this has been the argument surrounding promotional materials such as the film poster. Gray (2010) states, the industry has created a ‘relatively limited and standardized set of poster styles’ (Gray, 2010: 53), suggesting that the creativity of traditional posters has been lost.

With the importance and historical significance of the film poster, it is therefore interesting using the case study of Star Wars, to explore whether academics such as Gray are right to be pessimistic of the film poster, or whether in fact it is as unique as it has ever been. Previous academic research focuses on the distribution and semiotic importance of promotional materials as a whole but often dig to deep, forgetting the importance of the design of posters looking into the composition and artistic style.

Therefore, throughout this study I will break down the film poster into two key areas of study, artistic style and composition, exploring how changes between the traditional and contemporary film industry has affected these elements, resulting in the question of whether contemporary film posters have in fact become formulaic. Using the case study of Star Wars, I will be able to analyse and compare a franchise spanning across the traditional and contemporary industry, identifying changes and trends in design. To achieve this analysis, I will use a combination of semiotic analysis, online ethnography and audience interviews with the outcomes of this research giving me a clear understanding on how posters have changed and if contemporary posters have in fact become formulaic.

To achieve my desired outcome, I will break this study up into clearly defined and informed sections. I will begin by constructing a detailed academic literature review, giving me an understanding of promotional materials and the changes film posters have undertook from a traditional film industry, into the contemporary film industry. After this I will then set out my methodology stating my research methods and reasoning behind them. Moving on from this, I will present my findings by splitting them into the two sections of artistic style and composition. Within this section I will not only present the findings but also critically analyse what I have found, identifying trends and important questions to consider. Finally, I will evaluate my project as a whole, giving a definitive answer to my research question, as well as identifying the next steps for academics to explore.

Literature Review

Film Industry

Before looking into the distribution of media through promotional materials, it is firstly important to get an understanding of what the film industry is, and how it has been shaped. When looking into the film industry, Lexico defines it as ‘[t]he area of commercial activity concerned with the production and distribution of films’ (Lexico, 2021), with Kerrigan (2017) explaining how the industry has ‘been dominated by the Hollywood majors’ (Kerrigan, 2017: 13) with Hollywood making ‘$11.1 billion dollars in 2015 which is equal to the rest of top 9 movie industries combined’ (InPeaksReviews, 2017). This has been the case since the early 1920’s with Hollywood gaining power internationally, through their own subsidiaries or partnerships with local companies, such as the introduction of Lucasfilm in 1971. Quinn (2001) adds to this arguing that Hollywood ‘transform[ed] cinema from a cheap entertainment into a modern industry… [by] institut[ing] a system of mass production and distribution in an attempt to regulate as well as control cinema’ (Quinn, 2001: 41).

This controlling of the distribution of films shows how important of an element this is to major industry powers such as Hollywood. Kerrigan (2017) supports this declaring that ‘the distribution sector is undoubtedly the most instrumental element in a film reaching its audience’ (Kerrigan, 2017: 26), due to the promotional materials distributed helping gather momentum for the film through informing the audience on its genre, themes, and characters. Gray (2010) takes this one step further arguing that ‘media growth and saturation can only be measured in small part by the number of films and television shows… as each and every media text is accompanied by textual proliferation at the level of hype, synergy, promos, and peripherals’ (Gray, 2010: 1). This shows how he believes that the promotional materials are as important to the growth of the media industry as the final media products themselves.

Promotional Media

When researching promotional materials, Staiger (1990) writes about how the ‘commercial film industries that developed in the early years of the twentieth century quickly saw the need to publicise, promote and differentiate their products’ (Staiger,1990:3), resulting in them duplicating popular sales techniques at the time such as posters and magazines. Overtime, these techniques expanded with Kerrigan (2017) identifying that ‘conventional film marketing materials include posters, trailers, merchandise, electronic press kits (EPK) and stills’ (Kerrigan, 2017: 75). These materials were used to attract the target audience through ‘comunicat[ing] the key benefit that they will receive from consuming the film and differentiate it from competitors’ (ibid, 79). The aim of promotional materials has therefore stayed the same as they have entered a contemporary society, with the industry still trying to get their product to stand out within a sea of blockbusters, franchises and independents from across the globe.

However, there has been disagreements between academics when it comes to how the traditional forms of media have changed as they enter contemporary society. Author Fred E. Basten cited in Yarnell (2010) makes the statement that ‘not only have materials, methods, and styles changed, but people have changed. Yet the desired result is still the same: to show, to tell, to record, to illuminate through illustration’ (Basten cited in Yarnell, 2010). Although academics agree with the idea that method and styles have changed, with the aim still being to inform audiences, many struggle to accept that the materials themselves have changed since traditional promotional materials. This can be seen within the arguments of Kerrigan (2017), where they state that new technologies ‘have without doubt impacted on film marketing practice overall, but depicting these changes as wholesale movement from ‘old marketing’ to ‘new marketing’ may be overstating things’, going on to say that ‘many of the conventional film marketing practices still survive and may be supplemented by innovative online campaigns’ (Kerrigan, 2017: 75). This idea of traditional promotional materials being ‘supplemented’ is also supported by the ideas of Marich (2013) who adds that ‘old-fashioned publicity that used to “get space” in traditional media, such as newspapers and magazines, has rolled into cyberspace, where it blankets the online landscape’ (Marich, 2013: 119).

Film Posters

When defining movie posters, Wang (2019) states that ‘[t]he film poster is an early tool, which aims to quickly convey the main content information of the film to the audience’ (Wang, 2019: 423). This is done through the art form of poster design, which involves the artist making sure the ‘fundamental design elements (title, tagline, images and credit block) that make up a film’s poster’ are present (Barnwell, 2018: 66). Poster design is an important element of promotion and one of the most difficult elements to master, as Marich (2013) argues that ‘print is much more difficult than television spots and trailers because you have to pretty much focus on a single image… mak[ing] a choice to appeal more to one segment of the audience than others’ (Marich, 2013: 68).

Through the image created on the poster, many academics argue about how important each element is to selling the story to the target audience. Gray (2010) cites John Ellis in his writing when he states that ‘everything has been assumed to be there for a reason, and can be assumed to be calculated. Hence everything tends to be pulled into the process of meaning’ (Ellis citied in Gray, 2010: 48). Going on to argue that although limited compared to that of trailers, they ‘still play a key role in outlining a shows genre, its star intertext, and the type of world a would-be audience member is entering’ (Gray, 2010: 52). However, opposing arguments state that they are not ‘primarily interested with producing coherent interpretations of a film… the goal of promotion is to produce multiple avenues of access to the text… in order to maximise its audience’ (Klinger, 1989: 10). Although correct about posters aim being to attract the biggest audience possible, Klinger fails to realise that posters need to present a coherent interpretation of the film to attract this audience. If the meaning and story of the film is missing or misrepresented from the promotional materials, this will have a negative effect on the viewing audience.

Traditional Film Posters

When looking into the history of the film poster, Marich (2013) gives a clear history of the industry influence on posters, stating that ‘in the first half of the twentieth century, movie theaters took a central role in marketing films that they exhibited… distributor would create templates with blank areas (usually at the bottom), where individual theaters would place their names and details’ (Marich, 2013: 40). These posters where therefore primarily created, distributed and edited apart from the film industry, allowing for personalisation by the movie theatres, however they struggled to produce and distribute on a mass scale. Therefore, the individual movie theatres increased ‘reliance on Hollywood distributors… [with] major studios operat[ing] big poster departments that churned out graphic ads’ (ibid, 40).

With the introduction of print film promotional materials, the industry found that it was necessary to ‘have a distinct and strong artistic sense, so as to enhance the visual enjoyment of the audience’ (Wang, 2019: 423) and make it stand out from other materials around it. Therefore, film industries started to hire artists to create unique poster designs. Staiger (1990) gives a detailed understanding of this period when stating that ‘The Mutual Company announced a special poster department in January 1914… hir[ing] Cheltenham Advertising Service to innovate a new poster style’, with them returning with the idea of ‘present[ing] broad masses of color that made a decoration, an embellishment to the walls… [leading] to an era of the “im-pressionistic” method of poster advertising’ (Staiger, 1990: 8). This era led to movie posters being created using ‘warm pastel shades but so arranged that, while harmonious and pleasing to the eye, the reds, yellows and blues stand out and command attention’, meanwhile the ‘figures are all idealized paintings, representing scenes from the film story’ (ibid, 8).

Although traditional posters were treated as pieces of art in their production, we can still see that the layout and key elements are still carefully positioned to create the meaning for the audience. Barnwell (2018) states that these ‘artworks must focus the viewer’s attention on those few aspects of the foreground and background images that best represent the film’ going on to argue that successful traditional posters ‘maintain a clean design with plenty of white space that emphasizes a strong central image. The central image should be striking, intriguing and memorable’ (Barnwell, 2018:66-67). To ensure this many traditional posters ‘place the characters within the narrative of the film, at a point of narrative enigma… thus foregrounding the enigmas which the film will resolve’ (Haralovich,1982: 52). This therefore shows that although these posters at the time had a clear and unique artistic style, they still had to tackle the difficult task of creating meaning and intrigue within the chosen artistic poster designs.

Contemporary Film Posters

Due to the increase in size of the film industry, and speed at which film studios are producing and distributing movies, the nonstop merry-go-round filtered into the production of the promotional materials as well. The hand painted posters of old shifted towards ‘using photos in posters because advances in graphic-arts technology made photo printing feasible’ (Marich, 2013: 40-41). This resulted in less effort and time being put into each poster, and is supported by Heath (1977) as he states that ‘since the individual film counts for little in its particularity as opposed to the general circulation which guarantees the survival of the industry… [the] film is a constant doing over again, the film as an endless variation of the same’ (Heath,1977:28). This statement shows how film studios have shifted into viewing individual films as products that keep the industry thriving, instead of viewing each product as a piece of art, resulting in the equivalent promotional materials being treated the same as well.

Also, with changes into how the contemporary film industry is organised, many promotional materials are outsourced to specialist companies, having the benefit of the people creating the material being professionals. However, as Gray (2010) states, ‘the shows creators may have little or nothing to do with their creation, thereby producing ample opportunity for creative disconnects, and for uninspired paratexts that do little to situate either themselves or the viewer in the story world’ (Gray, 2010: 207). This view is shared by many, with huge amounts of academic research going into how the same semiotics are used to create meaning across hundreds of posters, resulting in a lack of diversity within genres.

Looking into this idea in more detail, Barnwell (2018) states that ‘as you study the marketing and promotional activities within your genre, you’ll soon discover elements that are uniquely characteristic to your genre’, going on to identify elements such as ‘specific vocabulary and phrases, design elements (colours, fonts and graphic elements) and iconography (images and symbols)’ (Barnwell, 2018: 690). These characteristic elements that are used regularly within the promotional materials of specific genres are explored in more detail by Gray (2010), as he states that ‘action films regularly feature the lone male hero looking ready for action… comedies regularly offer a close-up of the smiling star(s)… horror films often feature either an icon of the murderer, or a symbol of innocence that has been disturbed’ (Gray, 2010: 53). This use of the same semiotics results in promotional materials such as posters all following the same layouts, creating an uninspiring final outcome.

When identifying why the film industry sticks to this familiar use of semiotics, Lee (2016) makes the argument that ‘the main purpose of a movie poster is not to be art but to maximise box-office revenues’, going on to criticise contemporary films studios approach promotional materials, debating that ‘[y]ou would think the most effective way to do that is to create something memorable and striking, but most of the time, marketers will choose the low-risk option’ (Lee, 2016). This low-risk option means that they are able to appeal to the biggest audience possible with the promotional materials being easily understandable as they are similar to previous campaigns. This is also supported by Gray (2010) where they assert that posters follow the same styles so ‘one glance at the poster in a multiplex or at a bus shelter will immediately tell a viewer what genre to expect’ (Gray, 2010: 53). This is key as in the digital age target audiences take in so much content promotional campaigns need to get the information across instantly, without confusion.

Audience Engagement

Audience engagement, also known as fan cultures can be defined as the ‘balance between fascination and frustration: if media content didn’t fascinate us, there would be no desire to engage with it; but if it didn’t frustrate us on some level, there would be no drive to rewrite or remake it’ (Jenkins, 2006: 247). This engagement between audiences and media on a participatory level is a new phenomenon created through the introduction of Web 2.0, with Jenkins (2006) also stating that ‘If old consumers were assumed to be passive, the new consumers are active… If the work of media consumers was once silent and invisible, the new consumers are now noisy and public’ (ibid,18-19). Jenkins here shows how the ability to participate has allowed audiences to be heard, resulting in industries having to alter their promotional techniques, aiming to create content that meets the audiences needs and wants.

The introduction of Web 2.0 has impacted traditional promotional methods such as print media, with the internet opening up a plethora of new methods to promote films. However, many academics believe that traditional methods such as the film poster is still able to thrive in this new digital environment, with Kerrigan (2017) stating that ‘[d]espite developments in marketing film through social media, posters and trailers are still central to developing the visual identity of the film’ (Kerrigan, 2017: 76). Gray (2010) adds to this idea of Web 2.0 expanding the possibilities of advertisement, making the argument that ‘posters are often only one element of a concerted advertising campaign… internet advertising has become par for the course with new media products, and innovative campaigns that tread into the spaces of everyday life are all the more common’ (Gray, 2010: 57). This shows that where traditionally posters would have been the main source of advertising, the introduction of the internet has meant that posters are now only one of many ways of advertising. This could therefore be connected to the previously stated “conventional style” of film posters, with the industries putting more focus on other advertising techniques.

Also looking into other benefits of Web 2.0 on the distribution of film marketing, Stafford (2007) identifies the differentiation between traditional and contemporary promotion, making the point that ‘traditional promotion is designed on a push basis – promotional material is pushed towards prospective audiences… [while] the internet has introduced the possibility of pull technologies for finding information’ (Stafford, 2007: 164). This is therefore showing that the internet allows audiences to find out information of their own, instead of relying on the industry to hand feed them it. This could be seen as a benefit to film industries as audiences act as promotional tools themselves, sharing and talking about upcoming films, acting as free advertising. However, industries are also aware of how quickly and dominant negative press can ‘circulate and kill a new film’ (ibid,166), showing the power audiences now have on promotional materials.

This rise in fan power within the film industry has also seen a rise in fan created content such as posters. Lee (2016) makes the argument that ‘the staid nature of the medium has led to an increase in independent designers creating alternative artwork, distributing it online and often selling physical copies’ (Lee,2016). This supports the idea of contemporary film posters being uninspired with academics claiming that these fan promotional materials ‘challenge or supplement those created by the industry, in creating their own genres, genders, tones, and styles, and in carving out alternative pathways through texts’ (Gray, 2010: 143), as seen in the comparison of the official Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) poster (Figure 1) and a fan-made alternative (Figure 2). Therefore, this ability to create unique, exciting, and artistic promotional materials that reconnect with the artistic flare of traditional posters, has resulted in some studios ‘being smart enough to collaborate with designers whose work makes a concerted effort to buck the trend’ (Lee, 2016).

Figure 1 - Official Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) poster

Figure 2 - Fan Made alternate Star Wars: The Force Awakens poster

Methodology

Looking into the idea of film posters becoming formulaic in a contemporary society, I will explore how they have changed throughout time, using the case study of Star Wars (1977-2019). I will compare the nine film posters of the main saga which are positioned across the traditional and contemporary film industry landscape. When comparing these posters in will use a combination of textual analysis to understand the structure and style of these posters, as well as an online ethnography and interviews to support and gain an understanding of how audience opinions have changed.

When it comes to my audience analysis, I will start by completing an online ethnography, researching the social media platforms of twitter, reddit, TikTok and Letterboxd. With defining ethnography, Winter and Lavis (2020) state that ‘ethnography is a methodology that explores people’s behaviours, experiences, and beliefs in cultural and social context’ (Winter and Lavis, 2020: 55). Therefore, within these social media platforms I will analyse the comment sections, subreddits and hashtags that respond to the promotional content, with this research allowing me to identify differing opinions on new and old posters, as well as interactions between fans.

As well as the opinions gathered from the online ethnography, I will also conduct four interviews with people from a selection of age ranges. Through this analysis I will be able to gather ‘more detailed information than what is available through other data collection methods’ (Boyce and Neale, 2006: 3) such as the online ethnography, as I am able to ask follow up question on key findings and control the topic of conversation. Within these interviews I will show the respondents each poster, asking them to tell me what they like and dislike. After this I will then get them to tell me their favourite and why. These responses can then be analysed compared to the online ethnography, allowing me to identify any similarities and differences.

Finally, when it comes to the textual analysis I will analyse all nine posters, using semiotics to understand how meaning has been created, as well as identifying how they have changed over time. This research will be used throughout my findings section, backing up audience responses and giving a more academic analysis on the promotional materials.

When combining the use of audience research and the textual analysis of the corresponding posters, I will be able to get a clear understanding of the changes in style and format between the traditional and contemporary posters within my case study. Also, this research will highlight how these changes have resulted in differing opinions on the success of each poster from the perspective of the audience. Overall, this will give me a clear understanding on whether film posters have become “formulaic”, through the results of the two research methods.

Analysis

When it comes to the findings from both my online ethnography and interviews, I found that the question was far more complex than first identified. Where at first it was a question of whether audiences find the different posters formulaic, it was obvious after gathering the responses that audiences have more precise feelings about each poster and the franchise as a whole.

Therefore, instead of going through each individual poster at a time, stating the positives and negatives, I will organise my findings into the main two key themes brought up within my research. These themes being the artistic style and composition of the posters. Within these themes I will explore how each trilogy of posters meets this and the general perception from audiences. Finally, between these key themes I will also explore the idea of a gap in academic research and audience understanding, with possible scope to introduce a new term to more clearly explain and understand an industry phenomenon.

Art Style

When exploring the artistic style of film posters, Staiger (1990) previously explained how the traditional film industry would prioritise making promotional materials standout by implementing artists to create ‘innovative new poster style[s]’ (Staiger, 1990:8). This is reflected in the original trilogy with posters all being designed by different artists. Star Wars: A New Hope was designed by Tom Jung, Empire Strikes Back designed by Roger Kastel and Return of the Jedi designed by Kazuhiko Sano. By implementing different artists on each poster, George Lucas (director and creator of Star Wars) was able to create a different style of poster for each film.

The Star Wars: A New Hope poster (Figure 3) has a distinct style with Luke and Leia being a heightened version of themselves, with the characters and background being hand painted. This is supported by my interview with Clare (55) who states that the artistic style of the poster is ‘really different. The actors still look like themselves but adds more than just photos. Also, the body positions make the characters feel powerful’ (Clare). This style was also added on with the Star Wars: Empire Strikes Back poster (Figure 4) with Aaron (24) arguing that the style of this poster is ‘better than the first one’ (Aaron), with Clare (55) again adding to this, stating that ‘it feels like more effort has been put into it’ (Clare). This opinion of the poster is shared amongst most fans with my online ethnography also stating that they ‘really like the painting, art style they went for’ (explosivo_steve, 2021) and from thirteen different Star Wars poster rankings on Letterboxd, with the Empire Strikes Back poster coming out in first place.

Figure 3 - Official Star Wars: A New Hope poster (1977). Designed by Tom Jung.

Figure 4 - Official Star Wars: Empire Strikes Back poster (1980). Designed by Roger Kastel.

Moving onto the prequal trilogy, the style of the posters changed with artist Drew Struzan being hired to design all three posters. Immediately this resulted in changes to the creativity of the posters with explosivo_steve (2021) stating that ‘every prequel trilogy movie has the same style, sort of painted’ (explosivo_steve, 2021). With Paul (58) adding to this, stating that they ‘have tried to implement an art style like the originals’ (Paul). This use of the same style resulted in a lack of originality and the posters not being as popular among fans. Table 1 shows supports this with the prequal trilogy posters being ranked sixth, eighth and ninth among all nine posters. Looking into the argument made by Paul, stating that they are designed to reflect the art style of the original posters, it could be seen that while artist Drew Struzan was trying to honour the original poster styles, he in fact failed, not considering that it is not the exact style of the originals that fans favour, instead it is due to them being unique and creating an art style that is not been seen before.

However, although many believe the original Star Wars posters were unique, Lauren (20) raises the view that the ‘art style of all three of these posters just makes it look like every old film from the 70s or 80s, it isn’t very special to me’ (Lauren, 20). Although a view not shared by many, it is important to consider that audiences like Lauren, who didn’t grow up with Star Wars and are not fans of the franchise, do not hold any preconceptions when viewing the posters. This is important as through my research it was found that fans struggled to separate the promotional materials and the film itself. An example of this would be user explosivo_steve (2021) on TikTok, who begins his analysis of the Star Wars: Attack of the Clones poster by stating, ‘I’m going to try to let my bias not get in the way’ (explosivo_steve, 2021). Using this idea of fans looking back on promotional materials in different ways due to the nostalgia attached to them, I also want to explore the theory of altering my own position when analysing the original Star Wars posters.

Looking back at these early posters from around 40 years later, it is obvious that trends in the style of promotional materials has changed. Posters in the contemporary film industry follow a more consistent composition (one explored later) and favour the use of real images, stated by Marich (2013) earlier as she presented the shift in style due to ‘advances in graphic-arts technology’ (Marich, 2013: 40-41). With this change in trend, I propose the question that if we were to view these original Star Wars posters at their time of release, would they still be seen by audiences as unique and creative like they are viewed today? Analysing the posters seen in Figure 5 (collage of 70s film posters), we can see that although changes are evident in the composition and colours of the posters, the overall artistic style stays the same. The use of hand painted or drawn designs across all posters shows a consistent formula, resulting in a final product that’s considered as art as well as a promotional material. Therefore, it could be argued that within the 1970s this style of art posters was not seen as unique, due to it being a style widely used. However, could be countered stating that technology was not available or too expensive to make posters using real images, with the original Star Wars posters pushing the boundaries as far as they could while still using the style accessible to them.

Figure 5 - Collage of 1970s film posters

Looking into these changes in trends of film posters in more detail, studying the sequel trilogy of Star Wars posters clearly shows a switch in style. While the original trilogy uses the artist style of hand painted or drawn posters, and with the prequal trilogy trying to honour this, to varying success, the Star Wars sequel trilogy takes a completely different trajectory. Following the recently seen trend of contemporary posters using real images, with posters being made in computer software instead of pen and paper, Star Wars follows suit with their final three posters. Changing to computer software is not the only reason this trend became more popular but can also be seen as a result of changes in the industry. As stated previously by Gray (2010), posters are now outsourcing to specialist companies, providing ‘ample opportunity for creative disconnect, and for uninspired paratexts’ (Gray,2010:207), this can therefore be reflected in the Star Wars sequel trilogy with TheFiveFilms (2020) stating that all three posters look ‘less authentic and more like a fan-made photoshop image. Less focus and more just “Star Wars stuff”' (TheFiveFilms, 2020). Another negative influence from the industry that can be seen to have resulted in this photoshop poster trend comes from the growth in the industry itself. Academics have all commented on this change with the overall view being that due to the speed industries create and distribute films, there is not time to spend months on one poster. Instead, companies are favouring quickly creating posters in software like Photoshop and relying on the consistent style and formula of posters being enough to attract their audience.

This switch in trend towards Photoshop style posters with characters laid over each other can be seen across all three of the sequel posters. When looking into the opinions of Star Wars fans online, it was found that fans of the franchise are not against the style of posters, but instead against Disney using it on Star Wars. The24thFrame (2020) perfectly summarises this, stating that ‘Honestly the biggest failure of Disney’s handling of the Star Wars sequel trilogy is that they abandoned the hand-painted theatrical posters the series has always used, even through the prequels’ (The24thFrame). This anger shows how complex creating and studying film posters can be, as previous research has shown that the artwork style of the originals was not unique, but instead a trend of the time, and in many ways could be viewed in the same way as photoshop posters are seen today, with this current period of posters just being a trend that will gradually change. Many Star Wars fans still feel the need for new posters to remain in this traditional artwork trend. Is this due to fans wanting a piece of art they can display on their bedroom walls and not a piece of promotional material, fans wanting the franchise to stay consistent throughout the design of the promotional materials, or the need for the posters to trigger nostalgic memories of their childhoods? Either way, one thing stays the same, and that’s the lack of artist personality. This is supported by Clare (55) who stated that ‘There’s not much artistic style in this poster, feels like a computer has made it, especially compared to the others’ (Clare, 55).

The importance of an artistic style within Star Wars posters is further evident when identifying the features of the Star Wars: The Last Jedi poster (Figure 6) and the Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker poster (Figure 7) they like. The Last Jedi poster uses a unique colour palette of red, white and black, as well as incorporating paint stroke style texture down the sides of the poster. Although done digitally, these paint strokes help reflect the Empire Strikes Back poster design, with Aaron (24) identifying this stating that the ‘lines along the sides go back to Empire Strikes Back which is a good touch’ (Aaron). Another call back to the original Star Wars posters comes from the white boarder present in the Rise of Skywalker poster. When asked their favourite Star Wars poster out of this sequel trilogy, user ikarisstark (2020) states that its Rise of Skywalker ‘because they added white boarders as a nod to the New Hope poster. Didn’t expect myself to freak out about that small detail when it came out- bit I did’ (ikarisstark, 2020). This therefore shows the importance artistic elements within the posters have to Star Wars fans, with the smallest connection to the older films resulting in their opinions of poster changing.

Figure 6 - Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017) poster

Figure 7 - Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (2019) poster

This correlation between the connection to the past and positive perceptions of the prequal trilogy posters can be seen to be largely influenced by nostalgia. Marketing industries purposely integrate these nostalgic elements stated above as nostalgia can be used ‘to rejuvenate products’ (Reisenwitz, Iyer and Cutler, 2004: 56). Therefore, Disney can be seen to be aiming to rejuvenate the Star Wars franchise after ten years by using these design features that remind audiences of the older trilogies, reviving the inner child within them.

Throughout this analysis of the changes in artistic style between the three trilogies of posters, we have been able to see that fans and general audiences prefer the original Star Wars posters due to their unique and creative artistic style. However, we have also explored the theories that these posters are in fact not as unique as we might first believe, with posters going through stages of similarities and trends. This results in audiences being influenced with nostalgia as well as preconceptions of the film, not the promotional materials. The research also identifies how changes to the film industry can play a major role in controlling these trends. Contemporary film posters can now be seen to neglect any artistic style due to the lack of personality and time allowed in the design of each poster due to the rapidly moving production and distribution of products. This favours the use of digital software such as Photoshop, as promotional materials can be produced faster, but on the other hand a loss of creativity, due to the use of real images instead of drawn images. This therefore raises the question; can the composition of contemporary posters be used instead of the artistic style to provide a unique and creative promotional material?

Celebrity Pyramid

Before looking into the composition of the Star Wars posters in detail, it is firstly important to gather an understanding on how composition is used within film posters in a contemporary industry, with scope to explore the possibility of defining a more accurate and consistent term for this trend. Pushed to the forefront within contemporary film posters, however I argue can be seen within many traditional posters (an idea explored later), industries have started to favour the composition of layering celebrities’ heads on top of each other. This style is prevalent within a large proportion of franchises and films released today, as seen in Figure 8 and supported by OwLiX (2021) where they create a Letterboxd list of posters that are all designed in this style. They explain the style as ‘every main character’s face as varying sizes determined by their importance. Some facing left. Some facing right. Text usually centred towards the bottom’ (OwLiX,2021).

Figure 8 - Collage of contemporary film posters

When researching this trend and trying to identify a consistent term used by academics and fans together, I failed, with a shared term not being available resulting in multiple different names being used. A TikTok created by user Sophia.j.hoffman (2021) tries to define this term herself, using the name ‘celebrity tower’ (Sophia.j.hoffman, 2021), however is immediately met with thousands of users commenting alternative names such as, ‘bouquet of people’ (cryptidkid, 2021) and ‘floating heads’ (chief_robotmam, 2021). All of these alternative names for this trend successfully describe the style of poster present, however fail to take into account the purposely constructed hierarchy created within the design.

With the growth in power of the film industry, the power of the individual actor has also grown at an exponential rate. This has resulted in star power increasing and the industry having to bend to the needs and wants of A-lister celebrities. Therefore, this has resulted in posters having to include their faces, either due to contract restrictions or worldwide popularity of the star. Due to this change in star power and the rise in franchises staring multiple A-list actors, posters have been forced into this trend of layering celebrities on top of each other, with the size of the character often being determined by the highest paid actor in the film or often, but not always the protagonist. Therefore, with this understanding of both the composition and influence star power has on the hierarchy of the design, I propose a new term that takes into account both factors, celebrity pyramid.

The term celebrity pyramid clearly describes the visual arrangement of characters on the poster, often with multiple, usually smaller characters at the bottom leading to the singular main character at the top. Also, the choice of the word pyramid connotes the ideas of power and hierarchy, with the point of a pyramid often being considered as the pinacol and most important. This therefore perfectly reflects what is often seen as the protagonist or highest paid actor at the top of the pyramid. Having now defined a more accurate term for the composition we see in contemporary film posters, I will explore the composition of the Star Wars posters, identifying how they fit into this new trend of poster style and whether it results in the final outcomes becoming formulaic.

Composition

Looking into the sequel trilogy of Star Wars posters (Figures 1, 10 and 11) we can see the celebrity pyramid style of poster being used. All three posters use the formula of small, secondary characters along the bottom, with the larger, important characters standing out at the top. This trend of composition is effective at showing the audience who is in the film, with Paul (58) stating that they do this due to them ‘trying to sell [their] stars so that’s why they’re all there’ (Paul, 58). This is accurate with the rise in star power stated above resulting in this trend, however it can result in overfilling powers with explosivo_steve (2021) consistently stating that all three posters are too busy, with him arguing that The Rise of Skywalker poster has ‘a lot going on down here, again they can’t help it with the amount of characters they have’ (explosivo_steve, 2021). It is important to consider that although this trend of celebrity pyramids is often seen in contemporary posters, in the case of Star Wars it can be seen as far back as the third film of the original trilogy, Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (Figure 9).

Figure 9 - Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983) poster

The first two posters of the original trilogy (Figures 3 and 4) use a more simplistic composition of characters, limiting the design to around 6 characters. This reflects the theories of Ellis cited in Gray (2010) where he argues that ‘everything has been assumed to be there for a reason… pulled into the process of meaning’ (Ellis cited in Gray, 2010: 48). This is evident as they have arranged the characters in body positions of meaning, showing hierarchies of power as well as character relationships. This is supported by Aaron (24) stating that in The Empire Strikes Back poster (Figure 4) ‘the relationship of Leia and Hans helps tell the story’ (Aaron, 24), Also proving Haralovich (1982) argument that traditional posters ‘place the characters within the narrative of the film, at the point of narrative enigma’ (Haralovich,1982: 52), as seen through the relationship of Leia and Hans and the action poses of Luke and Leia in the A New Hope poster.

However, as we get to the Return of the Jedi poster (Figure 9) the composition begins to reflect the celebrity pyramid style we see today. Designer Kazuhiko Sano starts to implement the idea of hierarchy within the poster with the protagonist (Luke Skywalker) at the top, followed by the witty sidekick (Han Solo) and female icon (Princess Leia) below him. This change in style compared to the previous two posters could be regarded as a result of the main three characters rising in worldwide popularity, leading to the need of clearly showing that they are staring in the film instead of trying to tell the story through a creative poster composition. Therefore, this idea leads into Klinger’s (1989) counter argument to posters having to create meaning, when he states that ‘the goal of promotion is to produce multiple avenues to the text… in order to maximise its audience’ (Klinger, 1989: 10). With designer Sano choosing to use the avenue of celebrity pull to maximise the audience.

Since this poster composition Star Wars has chosen to follow the trend with all three prequal posters (Figures 10, 11 and 12), Clare (55) supports this by stating that the Revenge of the Sith poster (Figure 12) ‘doesn’t really make sense. In the other ones you can see what is going on story wise… where do I look’ (Clare, 55). This is reflected across the other two posters in the trilogy, however explosivo_steve (2021) does argue that he loves the composition of the Revenge of the Sith poster with ‘Anakin and Obi Wan in the middle, even though it’s kinda a spoiler for how it all ends’ (explosivo_steve, 2021). This raises an opposing argument on creating meaning within posters as you risk revealing too much and spoiling twists and key storylines within the film. This is extremely prevalent in a contemporary web 2.0 society where fans actively share and analysis promotional materials, looking for any hidden details that reveal information about the story. Therefore, you could argue that the industries creating posters are forced to use this simplistic celebrity pyramid composition as they are not able to experiment with different formulas, in fear that they will reveal too much to audiences who are looking for clues.

Figure 10 - Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999) poster

Figure 11 - Star Wars: Attack of the Clones (2002) poster

Figure 12 - Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005) poster

Through this analysis we have found that since the Return of the Jedi poster in 1983, all Star Wars posters have followed the same composition, slowly adding more and more characters to their posters due to industry changes forcing them to include all actors. Although these changes require more characters to be present on the poster, limiting creativity, it could be asked as to why the industries choose to use the composition of the celebrity pyramid instead of a layout that is more interesting and creative to audiences. This question raises a debate present among Star Wars fans surrounding the argument that Star Wars posters are allowed to use this celebrity pyramid style of posters, while others believe that they should be pushing the boundaries.

Looking into this argument in more detail, many Star Wars fans believe that the franchise actually created and caused to popularity of the celebrity pyramid poster, with user fishie.fish (2021) stating that ‘I only like it when Star Wars do it because they’ve been doing it since the 70s’ (fishie.fish, 2021). However, replies to this comment suggest that this isn’t true, with mokane1 (2021) arguing that the originals are ‘more dynamic, with maybe 4 characters, all in interesting poses, much better than what we have now’ (mokane1, 2021). Looking into this using my previous analysis, we can see that in fact the original trilogy did use this celebrity pyramid style with Return of the Jedi (last of the original trilogy) pioneering this format that is now used within all other Star Wars posters. This has therefore led to a theory that if Star Wars were the creators of this new celebrity pyramid poster style in the 1980’s, then surely the posters of the prequals and sequels should honour this creativity in forming a new style of posters within their trilogies.

Analysing this through the views of Lee (2016) stating that ‘a movie poster is not to be art but to maximise box-office revenues’ (Lee, 2016), we can see that the safe option for the industry is to maintain a similar composition so fans are able to instantly recognise that franchise and genre of film. However, TalkingHammel (2022) perfectly summarises how the sequel trilogy could have altered the composition and artistic style of their posters on a smaller scale, to honour the changes the original trilogy made to the promotional material of the poster. They state that, ‘TFA [The Force Awakens] was a reintroduction to the world, so having it be familiar made sense’ (TalkingHammel,2022), linking to the idea of industries needing consistency within posters to maximise the audience. They then state that, ‘in the next one, you go off in a new direction’ (ibid,2022), referencing how The Last Jedi (Figure 6) uses a unique colour palette, as well as altering the composition to include a landscape scene along the bottom. Finally, they finish arguing that the ‘Rise of Skywalker negates the new direction and kind of ruins everything’ (ibid, 2022), suggesting that the poster returns to the celebrity pyramid formula instead of pushing the boundaries, creating something new that other franchises will want to copy, finishing the cycle of Star Wars revolutionising the film poster through a new trend.

Through this analysis we have been able to identify that whilst the artistic style of the posters has massively changed since the original trilogy, the composition of the posters has stayed more familiar. Unique and creative compositions can be seen in the first two film posters, however Star Wars settled on a layout that suited their preference of showing off the celebrities in the film over the presentation of the story resulting in a lack of meaning be able to be took from the posters. The change in composition, favouring what we see as the celebrity pyramid today, has resulted in many Star Wars fans being protective over the configuration as they feel that Star Wars pioneered the style. This results in confrontation online as fans believe that Star Wars is exempt from criticism when others suggest that they look the same as other franchises in a contemporary industry, due to them starting the trend. Meanwhile, other fans believe that Star Wars should be pushing the boundaries of poster design, mirroring how the original trilogy broke the trend. Overall, no matter what side you are on, it can still be seen that the structure of these posters has become formulaic due to the predictability of the composition.

Conclusion

Throughout the last forty-five years, the film industry has changed to the point where it is barely recognisable. With this, you would expect the promotional material of the film poster to have changed to the same extent, however this is not exactly the case. Although finding what I initially expected, the sequel trilogy of Star Wars posters being the most formulaic with the composition of characters laid on top of each other. I did in fact also find that it wasn’t as black and white as this alone. As we look back at the original trilogy, it could be seen that the third instalment follows this formula with many fans arguing that Star Wars pioneered this style. After careful consideration and research into this style of layering characters on top of each other, looking into the hierarchy of celebrity power, I defined and termed this style of posters as the celebrity pyramid.

My preconceptions also expected to see the artistic style of the original and prequal trilogy being the feature that makes them unique and different. However, after altering my view of these posters from contemporary towards a traditional society, I found that this artistic style was in fact not unique with multiple films from the 1970s using the same artistic style. This therefore raises the question, does the formulaic nature of film posters change depending on whether the audience is viewing the product at the time of release or looking back on it from the future? This is a question founded within my analysis, due to audiences often viewing older posters such as the originals as unique due to them not having the cultural context of other promotional materials released at the time. Also, this question explores the idea of nostalgia and the recently seen trend of society wanting to be connected to the past through retro fashion and technology.

Through my case study of Star Wars, I have been able to answer my research question. The contemporary poster designs of Star Wars are formulaic with the consistent reuse of the same artistic style and composition, now defined as the celebrity pyramid. I have also found that it is unfair to state that just contemporary posters are formulaic with my research showing that traditional posters are also formulaic to an extent. However, where traditional posters used the same artistic style due to restrictions in technology and money, contemporary posters actively choose this formulaic style due to the low-risk nature and need to maximise its audience, although having the resources to break the boundaries.

With my analysis bring up these detailed considerations, it can be seen that my chosen case study of Star Wars allowed me to explore this bridge between traditional and contemporary promotional materials. I have been able to identify how style and composition of the posters have become formulaic, as well as briefly exploring how different aged audiences view these products and whether their own links to the materials can influence opinions. However, due to film posters being such a large focus of study, it is impossible to give a definitive answer to my question and is unfair to base the entirety of the art form on Star Wars alone.

Therefore, when identifying the next area of investigation for future researchers, I would have two different paths. The first, exploring Star Wars in more detail I would look at the correlation between nostalgia and influenced positive opinions on the related promotional materials. As well as this, another area of investigation would be the industries counteraction of the formulaic celebrity pyramid poster through the introduction of multiple teaser and fan made posters. These posters allow marketing designers to release their creativity that is often blocked by the strict industry rules that official poster have to follow. This results in final outcomes that create layers of discovery among fans, with designs being able to create mystery and meaning that official posters are not able to achieve. Therefore, this raises the possible debate that while official posters have to suffer creative block due to industry control, these additional posters are able to be the home for creativity.

References

Barnwell, R (2018) Guerrilla Film Marketing: The Ultimate Guide to the Branding, Marketing and Promotion of Independent Films & Filmmakers. New York and London: Routledge.

Boyce, C and Neale, P (2006) Conducting In-Depth Interviews: A Guide for Designing and Conducting In-Depth Interviews for Evaluation Input.

Gray, J (2010) Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts. New York and London: New York University Press.

Haralovich, M (1982) ‘Advertising Heterosexuality’, in Screen. 23(2), pp. 50-60.

Heath, S (1977) ‘Screen Images- Film Memory’, in Cine-Tracts. 1(1), pp. 27-37.

InPeaksReviews (2017) Top 10 Movie Industries in the World. Available at: https://medium.com/@inpeaksreviews/top-10-movie-industries-in-the-world-5d47cd9df44f (Accessed: 13th December 2021).

Jenkins, H (2006) Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York and London: New York University Press.

Kerrigan, F (2017) Film Marketing. London and New York: Routledge.

Klinger, B (1989) ‘Digressions at the Cinema: Reception and Mass Culture’, in Cinema Journal. 28(4), pp. 3-19.

Lee, B (2016) Gone to the wall – why modern movie posters are dreadful. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jan/28/why-modern-movie-posters-are-so-dreadful (Accessed: 8th December 2021).

Lexico (2021) Film Industry. Available at: https://www.lexico.com/definition/film_industry (Accessed: 8th December 2021).

Marich, R (2013) Marketing to Moviegoers: A Handbook of Strategies and Tactics, Third Edition. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

Quinn, M (2001) ‘Distribution, the Transient Audience, and the Transition to the Feature Film’, in Cinema Journal. 40(2), pp. 35-56.

Reisenwitz, T, Iyer, R and Cutler, B (2004) ‘Nostalgia Advertising and the Influence of Nostalgia Proneness’, in Marketing Management Journal, 14(2), pp. 55-66.

Stafford, R (2007) ‘The Culture of Film Viewing’, in Understanding Audiences and the Film Industry. London: BFI, pp. 147-174.

Staiger, J (1990) ‘Announcing Wares, Winning Patrons, Voicing Ideas: Thinking about the History and Theory of Film Advertising’, in Cinema Journal. 29(3), pp. 3-31.

Wang, L (2019) ‘The Art of Font Design in Movie Posters’, in Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. 398, pp. 423-425.

Winter, R and Lavis, A (2020) ‘Looking, But Not Listening? Theorizing the Practice and Ethics of Online Ethnography’, in Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 15(1-2), pp. 55-62.

Yarnell, K (2010) Movie Posters: Capturing the Essence of a Story.