Mapping a Sustainable Support Model for Practice-based Researchers, Supervisors and Examiners

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33008/IJCMR.2022.10 | Issue 9 | Oct 2022

Érica Faleiro Rodrigues (CICANT, Lusófona University/FILMEU), Deidre O´Toole (IADT/FILMEU) and Manuel José Damásio (CICANT, Lusófona University/FILMEU)

Abstract

This research statement complements the podcast with the same title and is construed as a stepping stone towards a sustainable support model for practice based researchers, supervisors and examiners within the FilmEU alliance and, most importantly, beyond it, opening up the debate on the opportunities and challenges facing the topic. For this task, four relevant players from the artistic research arena were interviewed: Till Ansgar Baumhauer, Nico Carpentier, Michelle Teran and Florian Cramer. FilmEU includes Lusófona University, Portugal, Baltic Film and Media School, Estonia, LUCA, Belgium, and IADT, Ireland. In order to create a model with long-term impact for practice and artistic-based research, the alliance is pursuing a common and transdisciplinary research culture on artistic research within the field of Film and Media Arts. A major hurdle identified by the alliance is the upskilling of practitioners to ensure they have the skills and knowledge necessary to perform and supervise practice-based research. Many potential candidates and supervisors are already distinguished within the worlds of practice or academia; hence, the next step will be creating a bridge between practitioners and researchers. FilmEU will have to provide the adequate technical resources and expertise to guide researchers through this transition from practitioner to practitioner-researcher and to ensure that the work created achieves a professional standard.

Introduction and Context

FilmEU – The European University for Film and Media Arts (Project: 101004047, EPP-EUR-UNIV-2020 — European Universities, EPLUS2020 Action Grant), includes four European higher education institutions: Lusófona University, from Portugal; BFM - Baltic Film Media and Arts - Tallinn University, from Estonia; LUCA School of Arts, from Belgium; and IADT - Dún Laoghaire Institute of Art Design and Technology, from Ireland. These institutions collaborate around the common objective of jointly promoting high-level education, innovation and research activities in the multidisciplinary field of Film and Media Arts and, through this cooperation, consolidate the central role Europe plays as a world leader in the creative fields, promoting the relevance of culture and aesthetic values for our social empowerment. In order to pursue its objectives, FilmEU will promote the expansion and improvement of the joint research capacity of the partner institutions and their ability to disseminate with greater impact the creative outcomes resulting from the education and research endeavours they support, further reinforcing the prominence of artistic research in the European higher education area.

In order to attain such objectives, FilmEU will nourish the implementation of a common model for practice and artistic based research that consolidates alternative paths for PhDs in this field and reinforces the social impact of the knowledge produced in the institutions that integrate the alliance. All this will be grounded in a common research agenda focusing on artistic research that will nurture joint research clusters and groups. In order to facilitate this, initial work was conducted with the objective of situating artistic research in the context of other disciplines. It started by questioning what the role of artistic research may be in meeting contemporary global and social challenges, while surveying existing theories, methodologies and approaches in artistic research. The outcome of this work is being developed under its Work Package 6 - Research and Innovation. FilmEU’s Work Package 6 produced outputs such as the Report on Artistic Research: Opportunities and Challenges and the report Supervision Models in Film and Media PhD Education. The first report encompasses a written report and a video, the second a written report, all materials are publicly available on FilmEU’s website for open consultation and are the background for the podcast linked to this report.

In its quest to create a sustainable support model for artistic practice-based researchers, supervisors and examiners, the FilmEU team is consistently striving to acquire knowledge by promoting prominent debates with proven scholars in the field of contemporary artistic research supervision. These specialists have a birds-eye-view of the status quo and enable team learning from solid academic and artistic experiences. What has been made clear so far is the importance of artistic research being discussed at an institutional level but also that cross-pollination of methodologies and proven best pedagogical practices be encouraged, as this is fundamental for the impact and innovative relevance of the work undertaken - communication and dissemination are key.

Relevant is also not to fall into the trap that the Vienna declaration on artistic research and ELIA´s contributions are universally consensual. The contemporary debate is intense since, in artistic research, we are currently faced with two apparently contradictory pulsations: the need to set parameters and boundaries that grant artistic research the same level of precision and distinction in 3rd cycle studies that other disciplines have, and the space for artistic freedom.

Methodology and Research Questions

The format of the podcast is one that brings knowledge and experience in artistic research and PhD supervision models to the forefront and which, rather than making a judgement, rather leaves space for interpretation and the considerations of the listener. This podcast is the product of qualitative research and, therefore, it:

produces findings that were not determined in advance.

has research which is applicable beyond the immediate boundaries of the study.

Throughout, the researchers had an open-ended perspective:

some aspects of the study were flexible, for example, the addition, exclusion, and or wording of particular interview questions.

participant responses affected how and which questions researchers asked next.

the process was iterative, that is, data collection and research questions were adjusted according to what was being learned.

The investigation into best practice in artistic research and PhD supervision models has, so far, led FilmEU researchers to conclude that the main predicaments, at this stage of the construction of the FilmEU project, can be institutional isolation and complacency in the reception of mainstream perspectives. The FilmEU project is in its infancy and, as such, it is paramount that it places questions that allow a steady learning curve in the field of artistic research. This can be achieved by having conversations and debates with actors outside the Alliance who may share insightful experience, creating a space for prolific exchange. Within FilmEU there is also an awareness that it is vital to ask questions now regardless of the fact that they may be difficult, lack a consensual status and/or deal with minority and apparently odd perspectives. What is fundamental is a space for the analysis of eclectic experiences and possibilities. Under the umbrella of these considerations, it is primordial for FilmEU that the scientific principle of continuous questioning remains at its heart, vis-à-vis the consideration that this will lead to a qualitative research environment that is dynamic and open to new perspectives.

Learning from what came before

To begin this journey the authors undertook a review of research on artistic research, white papers, journal articles and similar initiatives. There are many resources available that have been created to develop the sphere of artistic research’s research and supervision, including a toolkit by Sunil Manghani, which describes step by step how to undertake artistic research in a PhD context. As mentioned, there is also extensive work undertaken by ELIA including Mapping Research Supervision in Artistic Research PhDs, and The Salzburg Principles (2005) and Florence Principles (2016) which are aimed predominantly at supervisors and institutions. Other mappings of the field offer both broad and regional perspectives like the one which has been developed by Michelkevičius, which visually illustrates and documents his concepts of artistic research and represents them “as a tour of the diagrammatic world of knowing”.

Although there is an emerging wealth of research on artistic research, FilmEU is at an exciting point where the Alliance can construct a new research network, and paths for PhD candidates undertaking artistic research. As such, the authors reached out to leading academics who have insights into both the realm of AR and the practicalities of creating new pathways and structures. With this in mind, we devised three key questions for this podcast:

How to reconcile notions of artistic freedom and academic boundaries in artistic research?

What are the specific needs of PhD supervision in artistic research?

What should be the framework for the evaluation of artistic research PhDs?

The pool of four interviewees was selected following the criteria that they had to:

Be academic teachers with concluded PhDs in the field of arts.

Have years of experience as academic 3rd cycle supervisors in artististic research.

Have an understanding of European 3rd cycle academic procedures across various countries (to enjoy transnational knowledge in the field).

Maintain a public career as an artist.

Possess a career as an academic artistic researcher.

With this in mind, Florian Crammer, Michelle Teram, Nico Carpentier and Till Ansgar Baumhauer were selected to participate in this research project. Supplementary information on the interviewees selected will be provided in a further section of this work.

FilmEU 2021 Report on Artistic Research: Opportunities and Challenges

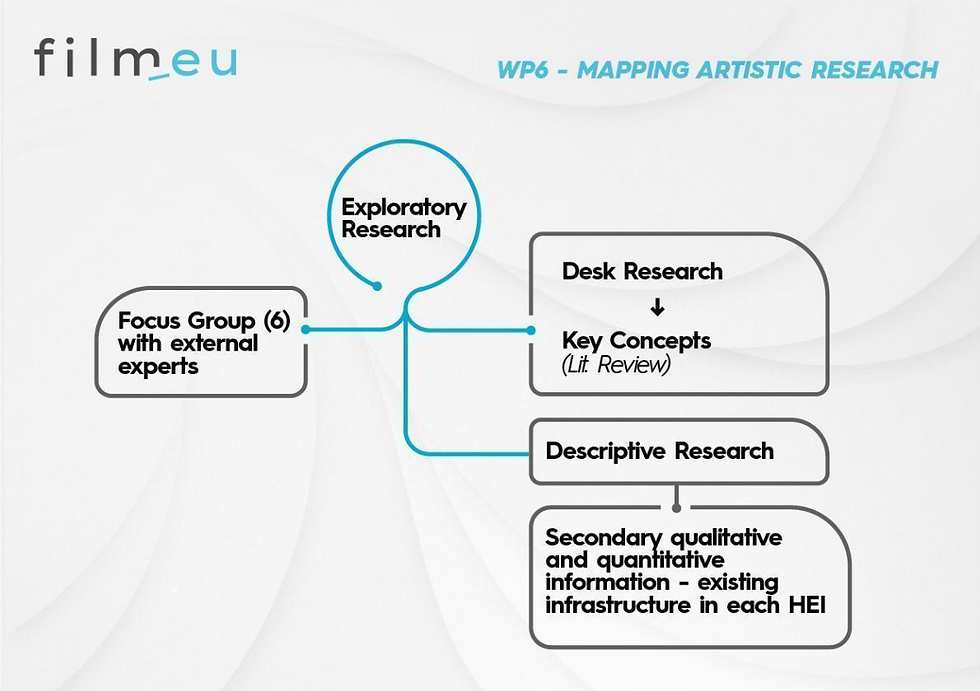

For FilmEu Work Package 6 the purpose of the output Report on Artistic Research: Opportunities and Challenges was to present a contemporary mapping on the topic and, to achieve this, it includes a number of methodologies, from desk research to focus groups with external experts. The results obtained are always transient, as the Alliance continues to work on building up its agenda on artistic research and improving its capacity to intervene in this domain.

Fig 1. Research Design Task “Mapping Artistic Research”. Damásio, Manuel José., Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Deirdre O’Toole and Maarten Coegnarts (2021). Mapping Artistic Research: Opportunities and Challenges. Reproduced by permission of FilmEU

The experts invited for this research work / mapping were:

Jyoti Mistry (interview held on the 24 February 2021), Professor in Film at University of Gothenburg in Sweden. Mistry works with film both as a mode of research and artistic practice. Recent publications on artistic research: International Journal of Film and Media Arts “Mapping Artistic Research in Film” (2020). Journal of African Cinema “Film as Research Tool: Practice and Pedagogy” (2017), Places to Play (2017) and forthcoming Decolonial propositions in collaboration with OnCurating, Zurich (April 2021). Currently, she is editor in chief of PARSE (Platform of Artistic Research in Sweden).

Susanna Helke (interview held on the 24 March 2021), Professor of Research and director of the Critical Cinema Lab at the Department of Film, Television and Scenography at Aalto University, Finland. Helke is an award-winning filmmaker and theorist whose films (American Vagabond 2013, Playground 2010, Along the Road Little Child 2005, The Idle Ones 2001, White Sky 1998, Sin 1995) received international recognition and have been screened in major international film festivals. Her work on the theory-praxis interface examines the intersection of the poetics and politics of documentary cinema in dialogue with, for example, contemporary political philosophy and critical theory.

Stefan Gies (interview held on the 22nd April 202) is the Chief Executive of the Association Européenne des Conservatoires, Académies de Musique et Musikhochschulen (AEC), a position he has held since 2015. Gies looks back on a wide range of professional experiences as a performing musician, music teacher and researcher, in an academic career spanning more than 30 years as a scholar, professor of music education and principal at German Higher Music Education institutions. The key topics he is currently working on include: campaigning for the recognition of the specific features of artistic education; ensuring the long-term preservation of adequate framework conditions to maintain a musical life and cultural offers; promotion of musical education at all levels and according to diverse needs; establishing artistic research and facilitating cross-border mobility.

Andrea B. Braidt (2021, April 28) ELIA president, Senior Scientist at the University of Vienna, Department for Theatre, Film and Media Studies. She previously served as Vice-Rector for Art and Research at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna from 2011 to 2019. As a researcher with degrees in film studies and comparative literature, her research focus and publication activity lie on narratology, genre theory and gender/queer studies. International fellowships and appointments brought her to the USA (UC Berkeley), Canada (University of Toronto) and Budapest where she was a guest professor for gender studies at CEU Central European University. From 2004-2011 she was Senior Scientist at the TFM Department for Theatre, Film, and Media Studies at Vienna University, leading numerous research projects in arts-based research, organising international conferences, and teaching extensively. She has been a member of the board of the Association of Media Studies GfM e.V. and is a founding member and former president of the Austrian Association for Gender Studies. She is vice-chair of the “Forum Research and Artistic Research” of the Austrian Association of Universities (uniko).

Elena Rusinova (2021, May 5), PhD in Arts, Associate Professor, Vice-Rector for Research and Science, Head of Sound Department at VGIK (Russian State Institute of Cinematography named after S. Gerasimov). She studied music and later graduated in sound design from VGIK, where she has been teaching since 1993. She is a member of the European Film Academy, the Russian Television Academy, the Film Arts Academy of Russia. She has published on the aesthetics of sound and film sound dramaturgy.

With the methodologies presented earlier, we attempted to address a number of key questions concerning artistic research which we may articulate as follows:

What are the existing research structures and resources in the four higher education institutions that integrate the Alliance and are there any common areas of thematic overlap?

What is artistic research and when does art qualify as academic research?

How may we relate artistic research to film practice?

What challenges need to be addressed to establish a long-term impacting model for practice and artistic-based research within the field of Film and Media Studies?

It is when trying to answer the question of what is artistic research that we are confronted with a myriad of terms, definitions and descriptions.

Fig 2. Defining Artistic Research. Damásio, Manuel José., Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Deirdre O’Toole and Maarten Coegnarts (2021). Mapping Artistic Research: Opportunities and Challenges. Reproduced by permission of FilmEU

According to Andrea B. Braidt, one of our guest speakers, there are three different ways of approaching the issue of artistic research (see Figure 3). There is the critical approach that upholds that artistic research is a way to criticise modern understandings of science and its master narratives. Artistic research posits itself as a ‘better’ alternative to mainstream research. Then there is the essentialist approach, which highlights the unicity and specificity of artistic research. Instead of building hypotheses that are verified/falsified (like in the sciences) or theses that have to be argued and made plausible (like in the humanities), artistic research brings forth a ‘singular explorative research’ based on ‘condensed experienceness’. Lastly, there is the pragmatic approach, which Braidt herself advocates and which, contrary to the previous approaches, does not consider artistic research to be any different from research in other disciplines. She gives four important arguments for this claim. Firstly, artistic research meets the original five core criteria of the OECD and thus qualifies as a Research & Design activity (novel, creative, uncertain, systematic, transferable/reproducible). Secondly, the quality standards that artistic research activities are measured by are developed by the research community as is the case with any other discipline. Thirdly, artistic research activities are neither more critical or challenging to the scientific system than any other research activity, although they can be. And, finally, artistic research is usually undertaken within a transdisciplinary setting.

Fig 3. Three Possible Approaches to Artistic Research (after Andrea B. Braidt). Damásio, Manuel José., Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Deirdre O’Toole and Maarten Coegnarts (2021). Mapping Artistic Research: Opportunities and Challenges. Reproduced by permission of FilmEU

Consequently, much of the debate on artistic research hinges on questions of methodological and institutional nature that have to do with further articulating this epistemological condition:

With what kind of knowledge and understanding does research in the arts concern itself? And how does that knowledge relate to more conventional forms of scholarly knowledge?

Through which methods and techniques of investigation do we reveal and articulate this knowledge?

How do we reproduce this type of knowledge?

How do we assess such knowledge? When does a particular practice qualify as research?

These are the type of questions that the Alliance will have to confront in order to further build up its own research agenda on artistic research.

Special note: Elena Rusinova provided us with an insight on artistic research at VGIK, in Russia, whilst Cahal McLaughin granted us an expert overview on the practice based research PhD model in the United kingdom. Both speakers explained with a certain level of detail how these models of research operate, the UK providing a seemingly more flexible approach when compared to Russia.

In its conclusion, this report acknowledged that to establish a long-term impacting model for practice and artistic-based research, the Alliance will further pursue a common and transdisciplinary research culture on artistic research within the field of Film and Media studies. To this aim the Alliance will:

set-up a series of collaborative activities among art researchers within the four institutions to further our thinking about some of the methodological and epistemological issues that were raised in this document;

via continuous and systematic methodological research, it will provide public reports on improving transnational communication and overcoming difficulties that arise from terminological and ontological differences in arts-based research;

develop a dynamic research structure from the ‘bottom up’ rather than through predetermined classifications imposed from the ‘top down’. This structure should be conceived as a fluid network of researchers clustered around topics rather than as a strict hierarchy;

train academic art research examiners, enabling them to provide rigorous and accountable assessments;

further build a common research agenda across all four institutions and beyond, to extend its network with worldwide partnerships;

empower artistic researchers with the appropriate training and resources.

FilmEU 2022 Report: Supervision Models in Film and Media PhD Education

This report was dedicated to the topic of doctoral education and supervision within FilmEU. The first section provides the reader with a literature overview of the European policy papers that are pertinent to the discussion of doctoral education. By presenting an insight into previous studies and surveys of doctoral education until today FilmEU aimed to provide a general conceptual framework that mapped important principles and guidelines of doctoral supervision. The second section of this report moves away from this “macro” European perspective and offers an overview of the current doctoral requirements and supervision capacities existing within the four institutions in the Alliance. Contrasting the current state of affairs with the background of the recommendations in the first section, allows FilmEU to conclude the report with a number of challenges and future opportunities for doctoral education and supervision in FilmEU.

Fig 4. Research Design Task “Supervision Models”.Coëgnarts, Maarten., Manuel José Damásio, Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Kaia-Liisa Jõesalu, Elen Lotman, Daithí Mac Síthigh and Deirdre O´Toole. Supervision Models in Film and Media PhD Education. Reproduced by permission of FilmEU.

The discussion of PhD supervision models for artistic research should be placed within a broader European context of position and policy papers, surveys, reports and handbooks that have been published since the Bologna declaration in 1999; a selection of which have been mapped in the timeline below. The boxes above the line represent papers on doctoral education in general. They provide an encompassing framework of principles and guidelines for the boxes below, which deal more specifically with papers on doctoral education in the arts.

Fig 5. A timeline of position papers and reports on PhD education in Europe. Coëgnarts, Maarten., Manuel José Damásio, Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Kaia-Liisa Jõesalu, Elen Lotman, Daithí Mac Síthigh and Deirdre O´Toole. Supervision Models in Film and Media PhD Education. Reproduced by permission of FilmEU.

An indispensable document when it comes to defining the policy of doctoral education in Europe was the publication of The Salzburg Principles in 2005. This document laid the foundation for discussing doctoral education in the context of the Bologna Process. Under this process, European governments participate in discussions regarding higher education policy reforms and strive to overcome obstacles to create a European Higher Education Area.

Fig 6. The Salzburg Principles (2005). Coëgnarts, Maarten., Manuel José Damásio, Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Kaia-Liisa Jõesalu, Elen Lotman, Daithí Mac Síthigh and Deirdre O´Toole. Supervision Models in Film and Media PhD Education. Reproduced by permission of FilmEU.

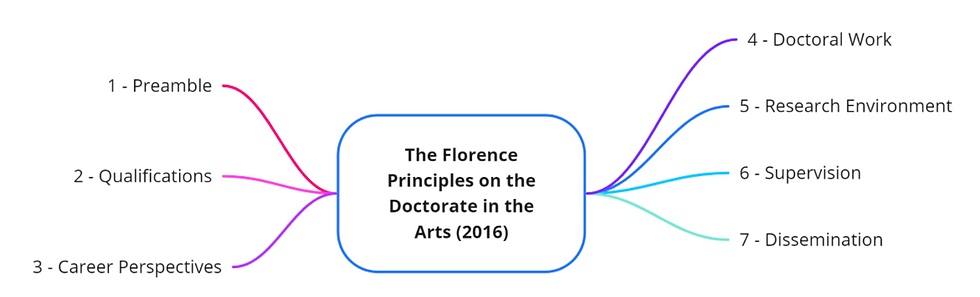

Building upon most of the papers mentioned above are The Florence Principles on the Doctorate in the Arts. The seven ‘points of attention’ out of which they are composed, “attempt to extract the critical core of doctoral education in the arts and seek to provide orientation pillars for a field which has been developing over the past 20 years or so.”

Fig 7. The Florence Principle on the Doctorate in the Arts (2016). Coëgnarts, Maarten., Manuel José Damásio, Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Kaia-Liisa Jõesalu, Elen Lotman, Daithí Mac Síthigh and Deirdre O´Toole. Supervision Models in Film and Media PhD Education. Reproduced by permission of FilmEU.

A more recent and comprehensive publication with an increased focus on supervision is the report entitled “Doctoral education in Europe today: approaches and institutional structures”. Published in 2019 by the European University Association (EUA) this survey provides an overview about the current landscape of doctoral education in Europe along a series of ten key aspects:

Fig 8. The ten key aspects of the 2018 EUA-CDE doctoral survey. Coëgnarts, Maarten., Manuel José Damásio, Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Kaia-Liisa Jõesalu, Elen Lotman, Daithí Mac Síthigh and Deirdre O´Toole. Supervision Models in Film and Media PhD Education. Reproduced by permission of FilmEU.

With regard to the dimension of doctoral supervision, universities were asked to address two key questions:

What institutional rules and guidelines are in place to organise various aspects of supervision, ranging from the appointment procedure for supervisors to their training?

To what extent do early-stage researchers find themselves supervised by a single supervisor or a supervisory team, either with members internal to the institution or from other universities?

Fig 9. Strategies for Artistic Research PhD Supervision. Coëgnarts, Maarten., Manuel José Damásio, Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Kaia-Liisa Jõesalu, Elen Lotman, Daithí Mac Síthigh and Deirdre O´Toole. Supervision Models in Film and Media PhD Education. Reproduced by permission of FilmEU.

These strategies are further complemented with a set of attitudes and attributes for Artistic Research supervisors adapted from the text Reconsidering Research and Supervision as Creative Embodied Practice by Jane Bacon and Vida Midgelow. This text arises from the project ‘Artistic Doctorates in Europe’ (ADiE, 2016-2019) and suggest several exercises for students and supervisors to explore practice in research including the following list of guidelines for “what it takes to be an artistic research supervisor”:

A willingness to reconsider and approach your supervisor/mentor/facilitator of practice – perhaps, changing and challenging your own expectations of candidates;

An ability to apply and be self-reflexive in relation to artistic practice;

Knowledge of your own strengths and weaknesses;

Interest and commitment to embracing criticality;

Willingness to both a challenge and a champion;

An understanding of the different time requirements and inherent tensions between artistic practices and university regulations;

An understanding of embodied practices and a commitment to the logic of practice;

A capacity to see rigour and clarity of purpose as potentials in the candidate rather than imposing them;

An interest in the practice of the candidate and the candidate themselves;

Embodied knowledges and specialist insights;

An ability to stay attuned to wider contexts, working together with micro and macro, zooming in and out;

An ability to track progress while allowing for openness and trust in the process;

An awareness of, and ability to challenge, if needed, the institutional regulations.

Reasons behind, practicalities and the implications of this podcast

The reasons for undertaking this research are to build an international research culture that promotes artistic research in a transparent way that champions artistic outputs as knowledge creation. Artistic research that works in an international sphere and can create collaboration and creation across borders. From this research the following steps will be taken;

Produce a podcast that showcases insights from the panel of experts;

Use primary and secondary research as grounds for establishing a PhD structure that can work across the Alliance;

Establish a network of experts in artististic research that can act as examiners or mentors whilst developing a PhD pathway.

The following insights emerging from this podcast are important for the creation and understanding of and implementation of artistic research. The next section will outline a highlight from each of the experts featured on the podcast: Florian Crammer, Michelle Teram, Nico Carpentier, and Till Ansgar Baumhauer. This podcast was researched and created by the FilmEu Team; Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Deirdre O’Toole and Manuel José Damásio, with technical help and collaboration from Tarun Madupu. Below is a small outline of what our experts expressed within the podcast.

Florian Crammer (joint interview held with Michelle Teran on the 29th of March 2022). Crammer is reader in Autonomous Practices at Willem de Kooning Academy & Piet Zwart Institute Rotterdam. Current research projects include “Making Matters” (with Leiden University, Het Nieuwe Instituut, Waag Society & West Den Haag), on collective material practices, and “Autonomy Lab”, on new concepts of autonomy in the arts. With Nienke Terpsma from “Fucking Good Art”, Crammer wrote the essay “What is Wrong with the Vienna Declaration on Artistic Research?”. Other recent publications include “Crapularity Aesthetics” (2018, online) and - with Wendy Chun, Hito Steyerl and Clemens Apprich - the book “Pattern Discrimination” (2018). Crammer volunteers for WORM, PrintRoom, De Player & Awak(e) in Rotterdam.

Michelle Teram (joint interview held with Florian Crammer on the 29th March 2022). Teran is an educator, artist and researcher. She is a practice-oriented research professor in Social Practices at Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam. Teran received her PhD in Artistic Research from the Faculty of Fine Art, Music and Design, University of Bergen. Her current and ongoing research areas are: socially engaged art, counter-cartographies, feminism, eco-social and critical pedagogy. Recent publications connect to emerging research around transformative pedagogy and include “Everything Gardens! Growing from Ruins of Modernity” (2020) with Marc Herbst and “Situationer Workbook/Situationer Cookbook” (2021), with various authors. Teran is the winner of the Transmediale Award and Prix Ars Electronica honorary merit.

Nico Carpentier (interview held on the 31st of March 2022). Carpentier is professor in Media and Communication Studies at the Department of Informatics and Media of Uppsala University. In addition, he holds two part-time positions, those of associate professor at the Communication Studies Department of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB - Free University of Brussels) and docent at Charles University in Prague. Moreover, he is a Research Fellow at the Cyprus University of Technology. Earlier, he was ECREA (European Communication Research and Education Association) treasurer (2005-2012) and Vice-President (2008-2012), and IAMCR (International Association for Media and Research) treasurer (2012-2016). Currently, he is Chair of the Participatory Communication Research Section at IAMCR. Carpentier is also the author of numerous academic articles and an artistic researcher.

Till Ansgar Baumhauer (interview held on the 4th April 2022). Baumhauer is an award-winning artist, curator, lecturer and publicist. He has had numerous solo exhibitions and has worked extensively as a performer and in musical projects. He obtained a postdoc scholarship at Bauhaus-University Weimar with an artistic research project on subversive structures in contemporary fine arts in the Persian-Pakistani cultural area. In 2020 Baumhauer became a team member of the international university alliance EU4ART at HfBK Dresden. Since 2021 he is content leader of the EC-funded alliance research project EU4ART_differences on artistic research. Amongst others, he has lectured at the State Art Collections of Dresden, Potsdam University, Hällisch-Fränkisches Museum Schwäbisch Hall, Goethe-Institute Hanoi, and the universities of Zittau-Görlitz, Hildesheim, Osnabrück and Dortmund.

As mentioned in this qualitative research, for all interviewees there was a common set of questions, however, throughout the process, flexibility was key, as different personal experiences and perspectives meant that the interviewers had to direct the conversations accordingly, making space for new questions and directions of reasoning.

The researchers that developed this podcast are all members of the task force of FilmEU’s work package 6 - Research and Innovation, and are the authors of FilmEU’s report Mapping Artistic Research: Opportunities and Challenges and the report Supervision Models in Film and Media PhD Education :

Érica Faleiro Rodrigues is a filmmaker, curator, and assistant professor in film and media arts at Lusófona University. She is a leading writer in FilmEU´s Work Package 2 - Institutional and Staff Capacitation, and Work Package 6 - Research and Innovation, having undertaken substantial research in this area and produced various open source reports under these two umbrellas. Previously, her work as a filmmaker granted her a Skillset Millennium Fellowship Award from the British government for a series of documentaries on the role of art in the life of refugees. She has also secured a grant to direct a feature documentary on Portuguese pioneer women filmmakers. The relationship between theory and practice is central to her academic work. She is a PhD candidate at Birkbeck, University of London.

Deirdre O´Toole, is a lecturer in the National Film School of Ireland, IADT. She has a practice-based PhD in Film and Visual Studies from Queen’s University Belfast, where she made documentaries collaborating with storytellers who had experienced trauma. O’Toole is a filmmaker who has worked for many years as a cinematographer where she filmed documentaries, music videos and dramas. She lectures on the BA (Hons) Film and Television Production, BA (Hons) New Media Studies and the Erasmus+ MA Cinematography. O’Toole is a leading writer in FilmEU´s WP6 (Research and Innovation) and has directed three documentaries, which have been screened extensively in film festivals and galleries around the world.

Manuel José Damásio is a board member and the coordinator of FilmEU. He is the chair of GEECT – the European association of film and media schools and a member of the board of CILECT – International association of film and media schools. Damásio is an associate professor and the head of the Film and Media Arts department at Lusófona University. He has vast experience in consulting and production in several areas of the field of audiovisual and multimedia production. He is the author of several papers and chapters in international peer-reviewed publications and was the principal investigator in numerous international R&D projects.

For FilmEU, it is essential that PhD candidates are given opportunities to participate in all aspects of research and innovation projects. With this in mind, a PhD candidate with suitable technical and theoretical skills was called upon to contribute to the project as a sound designer:

Tarun Madupu is a sound designer, composer and filmmaker from India and a member of the FilmEU taskforce. After graduating from Swarnabhoomi Academy of Music with a focus on audio engineering, he went on to get his Master’s degree from Kino Eyes – The European Movie Masters. Through his education and experience in film and music, he has equipped himself with an understanding of the mechanisms that weave film, narratives, and soundscapes together into something powerful. He is now centering these elements as the focus of his PhD study at Lusófona University in Portugal.

Significance of the Work Developed

Investigating the mapping of a sustainable support model for practice-based researchers within the FilmEU alliance, this podcast invited for discussion four scholars with proven careers in both artististic research and 3rd cycle teaching: Till Ansgar Baumhauer, Michelle Teran, Nico Carpentier and Florian Crammer. In so doing, it established a most needed bridge between artistic research within academia and artistic practice outside it. To foster knowledge, it was based around three main questions. How to reconcile notions of artistic freedom and academic boundaries in artistic research? What are the specific needs of PhD supervision in artistic research? What should the framework be for the evaluation of artistic research PhDs? The qualitative research developed under this umbrella, and the conversation steered in different directions according to each speaker’s viewpoint, provided important insights and acted as a timely catalyst for further discussion and for raising fresh questions, such as:

That the Vienna declaration on artistic research needs more intense scrutiny and renewed debate;

That for a Phd candidate in artistic research it is fundamental to be part of a collective of exchange. PhD support must be synonymous with creating a milieu of constant debate for and between candidates;

That artistic research can not be centred around a debate solely within academia but rather that it needs constant synapses between stakeholders internal and external to academia, including those who can provide support to PhD candidates.

Answers were given that lead to further relevant questions in the mapping of a sustainable support model for practice-based researchers. The work developed in this instance is vital for the debate in the field of practice based artistic research and it can certainly be used by a plethora of researchers.

Podcast Link

Bibliography

AEC (2015). White Paper on Artistic Research: Key Concepts for AEC Members. Brussels : The Association Européenne des Conservatoires, Académies de Musiques et Musikhochschulen.

Bacon, J., and Midgelow, V. L. (2019). Reconsidering Research and Supervision as Creative Embodied Practice: Reflections from the Field, Artistic Doctorates in Europe: Third-cycle provision in Dance and Performance. Online atwww.artisticcdoctorates.com

Barret, Estelle., Barbara Bolt (eds). 2009. Practice as Research - Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry. I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd

Bento-Coelho, I., and Gilson, J. (2020-2021). Visioning the Future: Artistic Doctorates in Ireland. Online at https://artisticdoctorateireland.com/

Biggs, M., & Karlsson, H. (Eds.). 2010. The Routledge companion to research in the arts. Routledge.

Boomgard, Jeroen., John Butler (eds.). 2021 The Creator Doctus Constellation - Exploring a New Model for a Doctorate in the Arts. Gerrit Rietveld Academie, EQ-Arts.

Borgdorff, H. 2012. The conflict of the faculties. Perspectives on artistic research and academia. Leiden University Press.

Coëgnarts, Maarten., Manuel José Damásio, Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Kaia-Liisa Jõesalu, Elen Lotman, Daithí Mac Síthigh and Deirdre O´Toole. Supervision Models in Film and Media PhD Education. https://www.filmeu.eu/achievements-outputs/

Damásio, Manuel J., Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Deirdre O’Toole, and Maarten Coegnarts. 2021 Mapping Artistic Research: Opportunities and Challenges. https://www.filmeu.eu/achievements-outputs/

Denzin, Norman K., Yvonna S. Lincoln (eds.) 2000. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications

EAAE (2012). Charter for Architectural Research. Brussels: The European Association for Architectural Education.

EC (2011). Principles for Innovative Doctoral Training. Brussels: European Commission, Directorate-General for Research & Innovation.

ELIA (2016). The “Florence Principles” On the Doctorate of the Arts. Amsterdam: Stichting A Lab.

EUA (2005). Bologna Seminar on “Doctoral Programmes for the European Knowledge Society” (Salzburg, 3-5 February 2005). Brussels: European University Association asbl.

EUA (2010). Salzburg II Recommendations: European Universities’ Achievements Since 2005 in Implementing the Salzburg Principles. Brussels: European University Association asbl.

EUA (2016). Doctoral Education - Taking Salzburg Forward: Implementation and new challenges. Brussels: European University Association asbl.

EUA-CDE (2019). Doctoral Education in Europe Today: Approaches and Institutional Structures. Brussels: European University Association asbl.

Michelkevičius, V. (2018). Mapping artistic research. Towards Diagrammatic Knowing.

Nelson, Robison. (ed.). 2013. Practice as Research in the Arts - Principles, Protocoles, Resistances. Palgrave Macmillian

Smith, Hazel., Roget T. Dean. 2009. Practice Led-Research, Research-Led Practice in the Creative Arts. Edinburgh University Press

Sunil Manghani (2021) Practice PhD toolkit, Journal of Visual Art Practice, 20:4, 373-398 DOI: 10.1080/14702029.2021.1988276

Von Borries, F. 2015. Artistic research—why and wherefore? JCOM, 14(1), C06.

Wilson M. and Ruiten, S. (eds) (2013) Share Handbook for Artistic Research Education. Amsterdam, Dublin, Gothenburg: ELIA, European League of Institutes of the Arts.