Updated: Jun 10, 2020

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33008/IJCMR.2019.17 | Issue 2 | September 2019

Pavel Prokopic

University of Westminster

Abstract

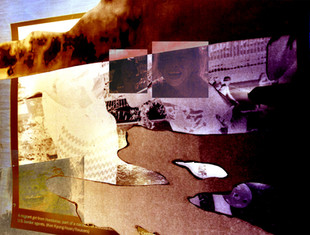

Affective Cinema is an AHRC-funded practice research project in film, informed by art cinema, experimental film traditions, film theory and philosophy. The outcomes of the research are films that combine aspects of cinematic style, nuances of performance and elements of chance. When all these attributes align in an unpredictable way, a feeling of meaning can be produced: a moment of cinema that is engaging and captivating without trying to tell a story or communicating something specific or intentional through the film. The research thereby aims to expand the potential of the cinematic form by producing experimental film structures in which this feeling of meaning can be identified, and by testing and developing methods that can lead to its emergence. The research also seeks to unite the practice and theory in a unique way – bringing the theory directly into the practice through a poetic voice-over. This submission to IJCMR represents a new version of Affective Cinema, one that was designed especially for the MediaWall at Bath Spa University, and which was exhibited between March 26–April 5 2019.

Affective Cinema is the 2019 winner of our MediaWall Award, our annual award in creative media research that aims to provide researchers with an opportunity to produce, curate and disseminate creative media-based research for a unique platform and audience.

Research Statement

Affective Cinema is a practice research project in film, informed by art cinema and experimental film traditions, and by conceptual fields derived from film theory and philosophy (specifically film ontology, and the philosophy of Deleuze, Bergson and Barthes). Rather than through narrative, the film is structured on the basis of affective significance – an original concept identified in various moments from the history of cinema, and subsequently developed through the project. Affective significance is a sense of meaning that is felt before it can be thought: it eludes language, and transgresses the boundaries of traditional knowledge and (inter-subjective) communication. Affective significance is produced by chance being captured and revealed on film, in combination with stylistic aspects and decisions that do not coherently assimilate these flashes of contingency into the film’s ordinary signification, but instead amplify their nonhuman origin in the real outside of the human world of reason, concepts and understanding. Through experimenting with film performance, and its ability to expose the nonhuman nature of the moving body as the real (below the human surface of intention, self-control, subjectivity, and meaningful gestures), the sense of affective significance can be amplified, when combined with the aforementioned aspects of style and chance.

Affective significance, as a concept embodied in the practice, relies on the unique ability of film to directly capture and expose reality – in movement – while employing style that prioritises the aesthetic potential of the moving image over seamless impression of (fictional or documentary) reality through the process of defamiliarisation. In this way, film gives rise to a direct, indexical imprint of the chaotic, unpredictable movement of reality – capturing a trace of the nonhuman basis of reality – making this image (and sound) of reality still, yet also capturing something of the fundamental temporality of reality. The moving-still nature of film allows for the direct imprint of the real to be aesthetically and temporally manipulated. No other established medium or art form can do that. This attribute of film represents its unique creative (and philosophical) potential; it is a way in which film contributes something entirely new to the world.

The research expands the potential of cinema by producing experimental film structures in which affective significance can be identified. Furthermore, it contributes to the ontological understanding of film by defining the conceptual field surrounding affective significance, but also by uniquely testing and applying this knowledge through practical exploration, and by expressing it through the practice directly. The poetic voice-over, which accompanies the Affective Cinema piece, loosens the linguistic format of the conceptual field and aligns it instead with the affective structures of the project, while using the meaning of the words to illustrate and illuminate the conceptual field of affective significance in an abstract, connotative correspondence with the images. Through intimate, close voice recording, and in creating points of resonance between the male and female voices by doubling up and synchronising the separately recorded speech (split between the two stereo channels), a balance is struck between the signifying nature (and the meaning) of the words and their affective impact as sound. In this way, the voice-over becomes an inherent part of the aesthetic/affective film structure – akin to music – rather than a mere rational account or explication of the theoretical basis of the project. At the same time, the singular unity between the affectively significant moving images, the affective/intimate sound of the voices and the meaning of the words creates a new kind of non-rational insight into the philosophical basis of the project that simply could not be expressed through language alone. Ultimately, therefore, the piece poses the fundamental, overarching question: ‘What makes film a unique form of art?’

Because the real is not in itself controlled, orchestrated or designed by human beings (as fundamentally opposed to the constructed reality of fiction and language), the impossibility to fully control reality has to register on film, if it is based on an indexical, photographic image (rather than animation or computer-generated imagery). And it is when something is (or appears to be) markedly originating in reality without human control and intention – by chance – that film can bring attention to it, by revealing it, by amplifying it, by abstracting it, even if (and especially if) it concerns a subtle aleatory arrangement that could have easily appeared insignificant (or entirely invisible) to the naked eye perceiving it directly. In the way film captures an unpredictable arrangement of reality as a still, permanent image (a sequence of still images); it gives rise to this very contingent arrangement as chance. If this moment of chance – as a particular sliver of space and time – was visible in quite this way only to the camera (or if only the privileged view of the camera revealed it), then this amounts to saying that this moment of chance has only ever existed as image, that the moment of chance arrangement in reality is inseparable from the still image. It is the moment of capture and framing where this aleatory arrangement originates as a singularity and as significance – as a mark of the very point of contact between becoming and being. In the shadow of human intention, chance becomes film’s nonhuman intention. This also results in a particular effect in the case of film performance, because the ‘privileged view’ film gives of reality unlocks in the body a sense of meaning and importance beyond intention and communication. It reveals to the human viewer – in a nonhuman way – the inherent, pre-verbal significance of the human body of the other.

As Bergson explains in Creative Evolution (1944), the real (the world as it is beyond the human realm of language, concepts and cognition) is an incessant flux, a constant flow of movement, becoming. We do not really ever see this movement of the real, because the basis of the intellect is to grasp the world conceptually as still. Even our understanding of movement (of an object moving from point A to point B) relies on conceptually stilled and abstracted space and time. While being part of the movement of the real (becoming within the real), we are only able to consider the world as still, through fixed concepts, language, and, most importantly, through seeing things as both permanent and carved out from the constant, undivided flux of reality. According to Bergson, film corresponds with the conceptual stillness of the mind: it is a still representation of movement, which nevertheless moves (appears to move), just like our impression of conceptually still reality. The relevant Deleuzian concepts essentially mirror this division between stillness and movement: the human world of language, concepts, subjectivity, being, versus the nonhuman world of impersonal, undifferentiated intensities and becoming.

Affect, defined by Deleuze and Guattari (1994) as the ‘nonhuman becoming of man’, thus very much dovetails with the realm of movement, in a useful opposition to emotion, which is instead a conceptualised, habitual form of affect. For the concept of affective significance, it is important to consider that the camera, despite being a human invention and mostly under human control, has itself a nonhuman view of reality, because of its automatic, mechanical capturing of light entering the lens in a given moment in time. In this way, it contains a still, indexical imprint of the becoming of reality (18 or more times a second), and through the replaying of this movement (the illusion of movement of the film apparatus) it reanimates what I refer to as the ‘echoes of real movement’. The echo of real movement can be described as a particular sense of significance derived from a completely singular event or occurrence – a moment of chance or serendipity, the encounter with the radically new that eludes representation. Barthes’ ‘third meaning’ (1977) describes precisely this echo of real movement when he studies specific still frames removed from a film. However, as this practice research project seeks to demonstrate, it is precisely the element of the illusion of movement in film that makes the echo of real movement resonate within the moving-still structures of film – stirring autonomous affects within the film itself – where Barthes’ concept of third meaning is destined to merely resonate within the mind of the attentive ‘reader’ of the still image.

The MediaWall presentation of this project at Bath Spa University was a good opportunity to experiment further with the structure, while retaining its original, horizontal format. The MediaWall is an architectural scale portrait gallery consisting of thirty 55” screens providing a canvas 7.5m high and 4m wide, occupying the triple height atrium space of Commons building at Bath Spa’s Newton Park campus. The way in which shots can coincide simultaneously in this three-way vertical split-screen format increases the complexity of the moving structure, giving rise to a new singularity as affective significance. The vertical split-screen unifies the work perceptually as a single body, minimising the separation (of attention) between the individual frames. Within this unified, vertical field, an additional dimension is introduced into the editing sequence, complicating its temporal flow, and leading to the production of new affects.

References

Barthes, R (1977) Image Music Text. Fontana Press.

Benjamin, W (2008) The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Bergson, H (1944) Creative Evolution. New York: The Modern Library.

Deleuze G and Guattari, F (1994) What is Philosophy? New York: Columbia University Press.

Del Río, E (2008) Deleuze and the Cinemas of Performance: Powers of Affection. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Doane, M A (2002) The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, the Archive. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Shaviro, S (1993) The Cinematic Body. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.